Timeline of the pandemic impacts and policy responses

This table shows the impacts of the pandemic in terms of restriction, employment, income support measures and the impacts on the asset market, both during the COVID recession period in 2020 and during the 2021 economic recovery period.

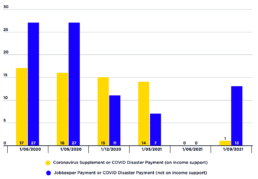

Recipients of Coronavirus Supplement, Jobkeeper Payment and COVID Disaster Payments (% of labour force)

This graph shows that, during the COVID recession in June 2020, 2.2 million people on working-age income support payments (equal to 17% of the labour force) received the Coronavirus Supplement and 3.6 million people who were still employed (equal to 27% of the labour force) received JobKeeper Payment.

These two COVID payments were reduced in late 2020 and removed in April 2021.

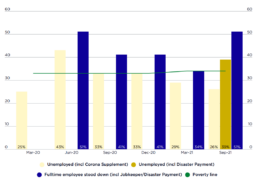

COVID income support for unemployed & fulltime employees (% of median fulltime wage)

This graph compares the poverty line for a single adult living alone with maximum rates of JobSeeker Payment together with Rent Assistance and the Coronavirus Supplement, JobKeeper Payment, and the COVID-19 Disaster Payment, which was introduced in the second wave of the pandemic. All values are expressed as a proportion of the median weekly fulltime wage.

The income supports available to a single adult without children who was unemployed were set above the poverty line in the recession, but drifted below it as the Coronavirus Supplement was reduced:

* In June 2020 (when the Supplement was $275pw) their income was around 30% above the poverty line.

* In September 2020 (after it was reduced to $125pw) they were close to the poverty line.

* In March 2021 (after it was reduced to $75pw), they were around 15% below it.

* In June 2021, (after the $25pw increase in Jobseeker Payment in April 2021 failed to offset the removal of the Supplement) they were once again around 30% below the poverty line.

Note that this comparison of payments and poverty lines for a single adult does not take account of the diversity of families of different sizes and housing costs, which also determine whether a household falls below the poverty line.

Comparison of poverty rates measured before and after housing costs

This graph allows us to gauge the impact of trends in housing costs on poverty.

The difference in poverty rates measured using these two poverty lines shrunk from 3.5 percentage points in 1999 to 2.1 percentage points in 2007. This suggests that the increase in poverty during that period was mainly due to greater disparities between low and middle-incomes, rather than changes in housing costs. After 2007, this pattern was reversed. The difference in poverty rates measured using the two poverty lines grew from 2.1 percentage points in 2007 to 4.7 percentage points in 2017. This suggests that the stabilisation of poverty rates after 2007 when housing costs were deducted from incomes (red line - top) was mainly due to increasing disparities in the housing costs of low and middle income households. As shown by the blue (lower) line, poverty declined over this period when measured before deducting housing costs. So, increasing disparities in housing costs played a major role in keeping the overall poverty rate at around 12-13% from 2009 to 2017, when it would otherwise have declined.

States' housing step-up no substitute for federal action

New research by the ACOSS/UNSW Poverty and Inequality Partnership shows renters on low and modest incomes are in the grip of a housing pincer, especially in regional Australia, as surging rents and the Commonwealth’s neglect of social and affordable housing creates acute stress.

The report notes that while some States have recently increased their investment in social housing, they simply lack the financial firepower to make up for a decade of neglect. Four state Governments (Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania and Western Australia) have announced significant self-funded public housing construction programs as a component of post-pandemic stimulus investment, providing an investment of nearly $10 billion over the next few years.

While these programs will add over 23,000 badly needed new homes to the stock of public and community housing over the next four years, more than 155,000 households are registered on social housing waiting lists across the country with more than 400,000 households in need of affordable housing.

The report reveals that across Australia newly announced social housing construction will be extremely patchy. For example, while Victoria and Queensland can anticipate social housing net growth of 8,300 and 4,400 units over the next three years, this will be little more than 400 in New South Wales. Even where states have stepped up, the Commonwealth Government must resume its historical role as the main funder of social housing development to come close to meeting demand. Shifting this responsibility to the states is untenable.

Housing stress due to both affordability and availability pressures is already rising significantly thanks to a looming rental crisis. While rents declined sharply in some inner city suburbs at the beginning of the pandemic, from mid-2020 they increased, and by August 2021 were accelerating at more than 8% - the fastest pace since 2008, and far ahead of wage growth of under 2%.

And rapid rent acceleration isn’t just confined to the cities. According to the report, regional rent rises are now outpacing metropolitan areas, particularly in NSW, Victoria and Queensland, surging ahead by a massive 12.4% (to August 2021) and raising the prospect of growing homelessness in these overheated markets.

For regional Australia, the proportion of tenancies low-income tenants can afford has declined from 41% to 33% over the course of this year. This percentage looks set to deteriorate further with the end of affordable rents for homes developed under the “National Rental Affordability Scheme” (NRAS).

The NRAS program funded 38,000 newly built rental homes for key workers and other disadvantaged renters to be let at 75-80% of market rates. Government figures show that over the next three years the subsidies and rent restrictions attached to some 22,000 of these affordable homes will expire.

ACOSS CEO, Dr. Cassandra Goldie said: “Community organisations across the country are telling us about the growing levels of despair experienced by people trying and failing to find affordable accommodation for their families in both metropolitan and regional areas.

“The situation for those on the waiting list for social housing feels increasingly hopeless, as individuals and families struggle to keep a roof over their heads in the face of rising private market rents or are forced to stay in circumstances that are not healthy or safe.

“The COVID crisis tested governments. Most state governments did a remarkably good job in protecting people who were homeless during COVID. But with such a chronic shortage of affordable homes, the resources they are putting towards social and affordable housing are just not enough to meet existing demand, let alone future need.

“We need the Federal Government to step up and step back into this space and do some heavy lifting to both address the massive social housing shortfall and meet the future needs of a growing and aging population.”

Lead author, Professor Hal Pawson, Associate Director of UNSW’s City Futures Research Centre, said: “A crucial part of any crisis is what lessons can be learnt that could and should lead to policy reform. State governments generally responded well in their emergency actions to help homeless people and protect vulnerable renters during the worst of COVID. And to their credit, some have gone much further by pledging billions for short term social housing investment. But there is little sign of any positive legacy on the systemic reforms and Commonwealth Government re-engagement is fundamentally needed to fix our housing system.”

Adrian Pisarski, Executive Officer of National Shelter, said: “The Leptos National Housing Finance Investment Corporation Review has found that Australia needs to finance $290b in social and affordable housing investment over the next 20 years. The Federal Government has the opportunity to provide the incentives to generate the vast bulk of that investment from equity investors but it must provide the financial incentives to allow that to occur."

Mission Australia CEO James Toomey said: “A silver lining of the pandemic was its role as catalyst for several State Governments to move fast to provide short-term temporary accommodation to rough sleepers and boost their investment in social and affordable housing. We thank the State Governments that really buckled down and took their role of supporting people who were homeless during COVID-19 seriously.

“But with huge social housing waiting lists and a housing crisis to contend with, Australia remains under a dark cloud when it comes to providing long-term housing solutions to address our stark nationwide shortage of social and affordable homes.

“Alone, our States and Territories simply don’t have the resources to address Australia’s social and affordable home shortfall. With the recent National review stating such a large investment is needed to address the shortage, our Federal Government holds the key. We need a national plan to end homelessness where the Federal Government takes a lead role in investment and that can also leverage private investment to create significantly more social and affordable homes.”

ACOSS recommends that the Federal Government urgently commit to funding a national social housing construction program, boost Commonwealth Rent Assistance and continue to support and extend affordable housing rental incentive programs to generate new supply, to help to protect people from financial distress and homelessness. It proposes:

- A major Commonwealth Government capital funding boost to deliver at least 20,000 new social housing dwellings;

- A 50% boost to the Commonwealth Rent Assistance payment to low income households to relieve rental stress;

- Creation of a new investment incentive to support construction of new affordable rental properties for people on low and modest incomes

Read the full report at: https://bit.ly/3nTsZId

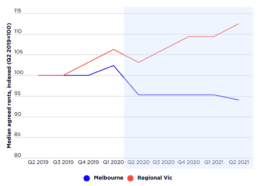

Median agreed rents, indexed - NSW & Victoria 2019-2021

These detailed two-year trends for NSW and Victoria relate to agreed rents.

Notably, Sydney’s outer suburban trend sharply contrasts from that of inner and middle ring localities. Rents in outer Sydney have been tracking along a trajectory much more similar to regional NSW (other than Newcastle). It could be that this is partly a reflection of changing property type demand during the pandemic. If homes for let in inner and middle Sydney are typically units, but most in outer ring suburbs (as in most regional areas) are houses, that could affect aggregate rent trends in a period when house rentals have commanded an unusually large premium.

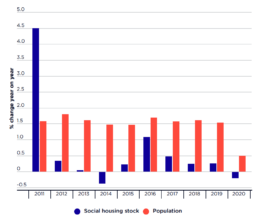

Annual growth rates – social housing stock and population, 2011-2020

For most of the 2010s population growth has run at more than three times the level of social housing expansion.

The first year in this sequence reflects the extraordinary impact of the national Social Housing Initiative (KPMG 2012). Launched in 2009 to counter the Global Financial Crisis, this four-year stimulus investment program represents the only significant addition to the social housing stock of the past 25 years. Across the last decade, however, Australia’s population grew by 16% whereas – even with 2010 as the base year – social housing expanded by only 7%. In the second half of the 2010s population growth outstripped social housing growth more than threefold – 7% versus 2%. Similarly, in every year from 2012 onwards, much faster growth in population than in social housing stock meant that the ratio of the former to the latter continued to grow. This was true even in 2020 when population growth was unusually depressed due to the pandemic, but when social housing stock actually diminished.

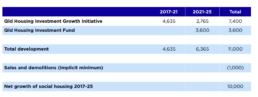

Interpretation of Queensland Government published statistics on social housing construction (dwelling commencements)

On 17 June 2021 the Queensland Government announced a $2.9 billion housing stimulus investment program. This supplements a pre-existing financial commitment to the Government’s 2021-2025 Housing and Homelessness Action Plan. The 2021 funding package involves three separate programs:

- $1.74 billion under the Queensland Housing Investment Growth Initiative (QHIGI) to expand social housing across the state by 2,765 dwellings, substantially involving schemes already planned and designed. Implicitly, this involves capital grants (averaging $629k per dwelling) to community housing organisations (and possibly other providers).

- A $1 billion investment fund (Queensland Housing Investment Fund – QHIF) to generate annual returns estimated at $40 million, implicitly to be channelled into ongoing revenue subsidies to participating housing developer-managers over a number of years. This model appears similar to the NSW Social and Affordable Housing Fund, and also the Victorian Social Housing Growth Fund (Pawson and Milligan 2015; Raynor 2017; Pawson et al. pp287-288). Again, published information suggests that some or all of the program – 3,600 homes to be developed over four years – will be delivered by community housing organisations.

- $60 million to acquire two year leases on 1,000 existing dwellings under the Help to Home program. (Queensland Government,2021a)

Information released alongside the 2021 Queensland Budget also states that there will be ‘7,400 new builds over the next four years under the Queensland Housing Investment Growth Initiative’ (Queensland Government 2021b). This implies that the newly announced funding for 2,765 dwellings will supplement an existing program already funded to develop 4,635 homes.

Attempting to reconcile these various figures suggests that newly constructed homes during the term of the 2017-25 Housing Strategy will total 11,000 (2,765+3,600+4635). Separately, the Queensland Government has also stated that it is ‘increasing the supply of social and affordable housing by almost 10,000 over the life of our Housing Strategy’ (Queensland Government 2021b). This appears to imply that at least 1,000 existing public housing dwellings will be demolished or sold in the course of the 2017-25 Housing Strategy development program.

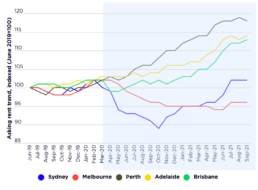

Asking rents for houses and apartments, 2019 - 2021

The differential economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic across Australia are apparent in 2020-21 rent trends for the five main capital cities.

Unlike the other cities, Sydney and Melbourne saw significant reductions in asking rents during 2020 in relation to both houses and apartments.

Only by mid-2021 had Sydney house rents recovered to their pre-crisis level. House rents in Melbourne remained almost 5% below their March 2020 values at this time, while apartment rents in both cities were still well over 5% lower than their pre-COVID levels.