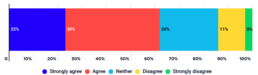

Community attitudes: Poverty is a problem that can be solved

This chart shows the responses in our Community attitudes towards poverty and inequality survey 2023 to the idea that Poverty is a problem that can be solved.

It shows that 75% of people in Australia agreed that poverty is a problem that can be solved with the right systems and policies.

Read the full report here: https://bit.ly/communityattitudes2023

Community attitudes: Government policies have caused some people to experience poverty

This chart shows the responses in our Community attitudes towards poverty and inequality survey 2023 to the statement Government policies have caused some people to be poor

It shows that 62% of people in Australia agreed that government policies have caused some people in Australia to experience poverty.

Read the full report here: https://bit.ly/communityattitudes2023

Most people support lifting incomes for those with the least

Three-quarters of people in Australia support an income boost for people with the least while less than a quarter think it’s possible to live on the current JobSeeker rate, new research by ACOSS and UNSW Sydney shows.

The latest report from the Poverty and Inequality partnership, Community attitudes towards poverty and inequality 2023: Snapshot report, also shows 74% think the gap between wealthy people and those living in poverty is too large and should be reduced.

The survey of 2,000 adults in Australia shows most people (62%) think government policies have contributed to poverty, while 75% think it can be solved with the right systems and policies.

- More than two-thirds (69%) think poverty is a big problem in Australia

- Just 23% agreed they could live on the current JobSeeker rate

- Another 58% said they would not be able to live on that amount, while 19% were unsure

- Three-quarters (76%) agree the incomes of people earning the least are too low and should be increased

- Most people think no one deserves to live in poverty, and that unemployment payments should be enough so people do not have to skip meals (86%) and can afford to see a doctor (84%)

ACOSS Acting CEO Edwina MacDonald said: “This survey shows popular support for the Federal Government to intervene to directly tackle poverty and the wealth gap that is threatening Australia’s social and economic fabric.

“Most people know it is simply not possible to live on the punishingly low rate of JobSeeker that traps people further in poverty. Instead, the majority of people think the government has a responsibility to look after those people struggling the most.

“We know from the pandemic that the key to solving poverty is lifting income support payments. The government has no excuse not to bring them up to at least the Age Pension rate of $78 a day in the face of such strong public support.”

Scientia Professor Carla Treloar of the Social Policy Research Centre at UNSW Sydney & lead author of the report said: “Community attitudes can wield significant influence on social policy.

“This research underscores the public’s awareness of policy impacts. The fact that the majority of people in Australia believe that government policies both contribute to and can solve poverty and inequality demands immediate policy reform. It’s time to address unjust policies failing those in need.”

UNSW Sydney Vice-Chancellor and President Professor Attila Brungs said: “The Poverty and Inequality Partnership between ACOSS and UNSW exemplifies our University’s vision for societal impact and the power of research to influence positive change.

“The insights and robust evidence that the Poverty and Inequality Partnership provides are vitally important for understanding how we can do better for some of the most disadvantaged groups of people in our society.

“Millions of Australians live with poverty and inequality. Highlighting community attitudes can help inform shifts in social policies that lead to better outcomes for us all.”

Mission Australia CEO Sharon Callister said: “This report makes clear that Australians want poverty eliminated in Australia, and that most people believe current levels of income support aren’t enough to survive and make ends meet.

“For people who are receiving income support and access Mission Australia’s services, the current rate of JobSeeker is profoundly inadequate and simply does not help get people back into work. It often traps them and their families in survival mode and pushes them into rental stress and homelessness.

“We hope that the government will start to take community expectations seriously and implement real solutions like adequate income support to end poverty and poverty-induced homelessness in Australia.”

Read the report at: https://bit.ly/communityattitudes2023

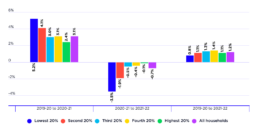

Average annual change in disposable income during COVID-19

This chart shows how income inequality declined sharply in year one of the Covid recovery (2020-21) but was restored to its previous level in year two (2021-22).

It shows that, in year one (2020-21), inequality declined. The average income of the lowest 20% grew by 5.2% after inflation, compared with 3% for the middle 20% and 2.4% for the highest 20%. In year two (2021-22) this pattern was reversed. The average income of the lowest 20% fell by 3.5%, compared with a fall of 0.5% for the middle 20% and a fall of 0.1% for the highest 20%. When we compare average growth in incomes for the two-year recovery period from 2019-20 to 2021-22, these effects largely cancel each other out leaving little change in income inequality overall. The income of the lowest 20% grew by an average of 0.8% per year, compared with 1.3% per year for the middle 20% and 1.1% per year for the highest 20%.

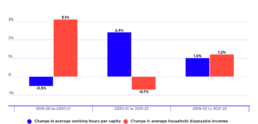

Average changes in hours worked and household incomes during COVID-19

This chart shows the changes in incomes and work hours during first years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It shows that, during ‘year one’ of recovery (2020-21), average household after-tax incomes grew by an extraordinary 3.1% after inflation, much faster than average income growth since the Global Financial Crisis. This occurred despite strict COVID lockdowns and the economic uncertainty surrounding the pandemic, which reduced average paid working hours per capita by 0.5% compared to hours worked in 2019-20.

During ‘year two’ (2021-22), these trends were reversed. Average household incomes declined by 0.7% after inflation despite the reduced severity of lockdowns and a solid 2.4% increase in overall paid working hours per capita.

Sharp jump in wealth inequality over last 20 years

The gap between those with the most and those with the least has blown out over the past two decades, with the average wealth of the highest 20% growing at four times the rate of the lowest, new research by ACOSS and UNSW Sydney shows.

The latest report from the Poverty and Inequality Partnership Inequality in Australia 2023: Overview, shows that wealth inequality has increased strongly over the past two decades. From 2003 to 2022, the average wealth of the highest 20% rose by 82% and that of the highest 5% rose by 86%, leaving behind the middle 20% (with a 61% increase) and the lowest 20% (with a 20% increase).

The overall increase in wealth inequality over the period was mainly driven by superannuation, which grew by 155% in value due to compulsory savings property investment.

Contrary to the public image of ‘mum and dad’ property investors, investment housing is very unequally shared: the wealthiest 20% hold 82% of all investment property by value.

The report also shows that the government’s timely pandemic response reduced income inequality, but only temporarily.

- In 2020-21, the average income of the lowest 20% income group grew by 5.3% compared with 2% for the middle 20% and 2.4% for the highest 20%, predominantly due to the introduction of COVID income supports.

- However, during 2021-22, the removal of these income supports largely reversed those trends, restoring income inequality close to its pre-COVID level.

- Incomes fell generally, but more so for those with the least. The average income of the lowest 20% fell by 3.5% compared with 0.5% for the middle 20% and 0.1% for the highest 20%.

Quotes

Dr Cassandra Goldie, CEO, Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS):

“Left unchecked, growing wealth inequality threatens to exacerbate and entrench generational, spatial and social divisions in our community. Governments can reverse that tide by fixing inequities in our housing and superannuation policy that disproportionately benefit those with the most.

“The pandemic response highlights the profound impact of government policy on income inequality in our society. Sadly, it was a story of two steps forward, and two steps back when the increased payments were withdrawn and income inequality returned to close to pre-pandemic levels.”

Scientia Professor Carla Treloar, Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Sydney:

“This report builds on the Government’s recent wellbeing framework to show that while income inequality has remained relatively steady, wealth inequality has increased over the past decades. We can reverse this trend through more affordable housing and a fairer tax and superannuation system.

“Additionally, increasing income support payments permanently will reduce income inequality.”

Professor Attila Brungs, Vice-Chancellor and President, UNSW Sydney:

“High-quality research, expertise and policy advocacy, such as those at the heart of the Poverty and Inequality Partnership between ACOSS, UNSW Sydney and our partner organisations, are essential if we are to influence and effect lasting change in how wealth is distributed in Australia.

“The report Inequality in Australia 2023: Overview shows that tackling poverty and inequality continues to be an area of great national need. It also demonstrates the capacity of research to inform evidence-based public policy that can have a very real impact on the lives and livelihoods of all Australians.”

Sharon Callister, CEO, Mission Australia:

“The COVID experience has been shown to be a tragic missed opportunity to raise incomes in the poorest households and reduce the risk of homelessness. In 2020, significant additional COVID income support payments successfully raised household incomes and reduced inequality, trends that were reversed when the payment was removed. Since that time, Mission Australia has seen a 26 per cent uptick in demand for our homelessness and housing services.

“Poverty is the main underlying structural cause of homelessness and alleviating poverty is an essential part of preventing and ending homelessness for good. Adequately raising income support is a crucial policy response. Income support should do what it’s designed to do: protect people from poverty, not condemn them to it.”

Julie Edwards, CEO, Jesuit Social Services:

“The response to the pandemic demonstrated that it is possible to reduce income inequality and to ensure that people do not have to live below the poverty line. For the marginalised people Jesuit Social Services works with every day, the temporary Coronavirus Supplement was the difference between being able to put food on the table and afford medication, and to put a roof over their heads. We call on our leaders to commit to sustained systemic reform to enable all Australians to live a dignified life.”

Penny Dakin, CEO, Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY):

“Kids born into families struggling on low incomes feel the impacts of financial stress directly. Not only does it make kids’ lives harder today, but when kids grow up in adverse conditions, they are much more likely to suffer issues such as unemployment, ill-health and jail as adults. Government policy should seek to level the playing field for all, especially for kids, rather than deepening the divide.”

Read the full report: https://bit.ly/3LBzxq2

Key findings

Income inequality

- In 2019-20, the highest 20% of households by income had average incomes of $4,306 per week after tax, five times the income of the lowest 20% ($794), and the highest 5% ($6,495) had eight times the income of the lowest 20%.

- Wages comprise 77% of incomes overall, but the lowest 20% relied relatively more on social security (50% of their income) while the highest 5% relied relatively more on investments (comprising 23% of their income).

Long-term trends in income inequality (1999 to 2019)

- Over the last two decades, income inequality increased during periods of income growth (1999-2007) and stabilized in periods of income stagnation (2007-2019).

- The average incomes of the highest 5% grew faster (by 59% overall) than those of the middle 20% (41%) and lowest 20% (46%) during this period.

Impact of COVID-19 (2019 to 2022)

- During the first year of recovery from the COVID recession (2020-21), temporary government income supports lifted average household incomes and reduced income inequality.

- COVID income supports helped the lowest 20% more significantly than other groups.

- However, the removal of COVID income supports during 2021-22 led to a decline in real incomes and an increase in income inequality, bringing it close to pre-COVID levels.

Wealth inequality

- Average household wealth in Australia is the fourth-highest in the world, driven mainly by home ownership.

- Wealth distribution is highly unequal, with the wealthiest 20% holding average wealth of $3,240,000 – six times the wealth of the middle 20% ($588,000) and 90 times that of the lowest 20% ($36,000).

- Contrary to the image of the ‘mum and dad investor’, the highest 20% by wealth holds 82% of the value of all investment property and 78% of all shares and financial investments .

Long-term trends in wealth inequality (2003 to 2022)

- Wealth inequality increased substantially over the past two decades. The wealth of the highest 20% increased by 82% compared to 61% for the middle 20% and just 20% for the lowest 20%.

- Growth in superannuation assets contributed significantly to the overall increase in of wealth inequality.

Use this handy calculator to see where people rank in the Australian income distribution: https://povertyandinequality.acoss.org.au/income-calculator/

Read the report: https://bit.ly/3LBzxq2

Comparison of poverty trend and SDG target path

This chart shows the percentage of people in poverty between 1999-20 to 2019-20 and compares this with the percentage of people in poverty if we were following the target set out in the UN Sustainable Development Goals, of which Australia is a signatory. The Sustainable Development Goal on poverty includes: "By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions" (note that this chart uses 50% of median income in lieu of an accepted national definition of poverty in Australia).

New report highlights depth of poverty for people on income support

People who are unemployed, people receiving income support, renters, sole parents, women, children and people with disability are at highest risk of poverty, while those on Youth Allowance experience deepest poverty, according to Poverty in Australia 2023: Who is affected, released today by the Poverty and Inequality Partnership led by ACOSS and UNSW Sydney.

The depth of poverty experienced by people on income support payments is severe. Households relying on Youth Allowance are in the deepest poverty, with incomes on average $390 per week below the poverty line. People in households relying on JobSeeker were $269 per week below the poverty line, and people in households relying on parenting payment were $246 per week below the poverty line.

By payment type, 60% of people receiving JobSeeker Payment and 72% of people receiving Parenting Payment live in poverty, compared with one in eight (13%) people and one in six children (17%) in poverty overall, based on the latest available data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

This highlights the failure of relevant payments and supplements to meet essential costs, including the real costs of raising children as a single parent.

The experience of poverty is also highly gendered. Households whose main income-earners were women experienced almost twice the level of poverty in 2019-20 as those whose main income-earner was a man (18% compared with 10%).

Housing status is a major poverty risk, with 1 in 5 people (20%) renting privately and half (52%) of people in public housing living below the poverty line, compared with 10% of mortgage holders and 8% of home-owners without a mortgage.

Sole parent families, migrants from non-English speaking nations and people with a disability are all experiencing poverty at above average levels.

ACOSS CEO Cassandra Goldie said the report provided compelling evidence about the profile of poverty in Australia, who is at greatest risk and how we can end poverty for all.

“The fact that a majority of people relying on unemployment payments and parenting payments are in poverty shows that current income support payments for people who are unemployed and single parent families are totally inadequate to meet the essentials of life.

“The depth of poverty experienced by young people relying on Youth Allowance also highlights the need for urgent action to lift allowances for young people, including students who are now facing severe financial distress.

“The experience of poverty is also highly gendered. Households with women as the main income earner are almost twice as likely to experience poverty as those where men are the main income earner.

“This report provides further evidence of the need for a poverty reduction package in the May Budget to lift working-age income support payments to at least $76 a day, double rent assistance, increase supplements for the extra costs of sole parenthood and disability, complemented by a commitment to full employment and improved employment services.

“The Government also needs to invest in at least 25,000 social housing units per year, with housing costs a major poverty risk for people on low incomes.

“ACOSS strongly welcomes the work of the Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee and the Women’s Economic Equality Taskforce which are both providing advice to government on policies to drive down poverty in Australia, one of the wealthiest countries in the world.”

Carla Treloar, from the Social Policy Research Centre at UNSW Sydney, said:

“This research reveals the profile of poverty in Australia and the role that policy settings – particularly payment rates – play in determining poverty.

“The depth of poverty experienced by young people on Youth Allowance is unacceptable. Young people who are trying to start their working life are being left behind. And, we see every day on campus the impact that this has on students who are struggling to pay for essentials while trying to complete their degrees.”

Read the report at: https://bit.ly/3JRxNsk

Key facts

The following lived below the poverty line in 2019-20

- 1 in 8 (13%) of all people, including 1 in 6 (17%) children

- 62% of people in households whose main income earner is unemployed

- 60% of people on Jobseeker Payment, 72% of people on Parenting Payment and 34% of people on Youth Allowance

- 34% of people in sole parent families and 11% of people in partnered families with children

- 18% of households where the main earner is a woman and 10% of households where the main earner is a man

- 20% of people with disability who need assistance with self-care, mobility or communication

- 20% of people renting privately and 52% of those in public housing

- 18% of migrants from a non English-speaking country are in poverty compared with 11% of people born in Australia

Households mainly reliant on income support payments had average weekly incomes well below the poverty line:

- $197pw less than the poverty line for all income support households (including pensions and working age payments)

- $390pw less for those relying on Youth Allowance

- $269pw less for those relying on JobSeeker Payment

- $246pw less for those relying on Parenting Payment

The report used the latest available data from the 2019-20 Australian Bureau of Statistics Survey of Income and Housing.

The poverty line is defined as 50 per cent of median household income, taking account of people’s housing costs.

Households mainly reliant on income support payments (‘income support households’) are households in which over 50% of gross income is government cash benefits and those benefits are at least $180 per week.