The wealth inequality pandemic: COVID and wealth inequality. Build back fairer, report 4.

Foreword

This is the fourth and final report in the ACOSS and UNSW Sydney Poverty and Inequality Partnership’s COVID Build Back Fairer Series. It traces changes in household wealth and its distribution through the pandemic up to December 2021 and examines the impact of policy settings, including interest rates and COVID payments, on growth in overall wealth and its distribution among different households.

The purpose of the Build Back Fairer Series is to help us understand the impacts of the COVID pandemic and government policy responses to it on people’s incomes, wealth, employment and housing and to assess which groups and regions were most affected.

The first report in the Build Back Fairer Series, Analysis of income support in the COVID lockdowns in 2020-21, examined changes to income support for people in different locations across Australia during the COVID pandemic. The second report of the series, Australian income support since 2000: Those left behind, shows the people who have been impacted most by changes to income support payments over the past 20 years, including during the pandemic, both negatively and positively. The third report, How poverty and inequality were reduced in the COVID downturn and increased during the recovery, assessed changes in inequality and poverty during the pandemic.

This report is the final report of Phase 1 of the ACOSS/UNSW Poverty and Inequality Partnership, the first 5 years of the Partnership which was launched in 2017.

We trust this report will assist decision-makers to design policy responses to build back fairer in a manner that eases wealth inequality and improves housing affordability for those on the lowest incomes. The Poverty and Inequality Partnership between ACOSS and UNSW Sydney includes researchers from multiple disciplines in order to explore fully the ways in which inequality and poverty are related to other measures of disadvantage, such as health, housing and homelessness and justice.

We are grateful to those ACOSS members and philanthropists who have supported Phase 1 of the Poverty and Inequality Partnership: Anglicare Australia; Australian Red Cross; the Australian Communities Foundation Impact Fund (and three subfunds – Hart Line, Raettvisa and the David Morawetz Social Justice Fund); the BB and A Miller Foundation; the Brotherhood of St Laurence; cohealth, a Victorian community health service; Good Shepherd Australia New Zealand; Mission Australia; the St Vincent de Paul Society; the Salvation Army; and The Smith Family.

We are very proud of the work the Partnership has done in its first 5 years and thrilled to be planning for the next 5 years of research and impact, with new research streams on deprivation, community attitudes to poverty and the lived experience of being on a very low income.

Edwina MacDonald, Acting CEO, ACOSS & Professor Carla Treloar, UNSW Sydney.

Key findings

- Households in Australia are on average the fourth-richest in the world, but many are financially vulnerable due to high debt or low financial buffers.

- Household wealth grew as much over the past 3 years as in the previous 15 years. Two thirds of the increase in wealth came from house price inflation. Residential property values rose 22% through the year to December 2021 – the highest annual increase in 35 years.

- Wealth inequality rose sharply from 2003 to 2018, then declined slightly in the pandemic. Rising house prices moderated overall wealth inequality, as housing is distributed more evenly across the population than other kinds of wealth) but shut younger people and those with low incomes out of home ownership.

- Household wealth is still shared very unequally: The richest 10% of households has an average of $6.1 million and almost half of all wealth (46%), while the lower 60% (with an average of $376,000) has just 17% of all wealth.

This report examines changes in household wealth and its distribution through the pandemic, updating our previous analysis of wealth inequality from 2003-20171See ACOSS (2020), Inequality in Australia 2020: Part 1 – Overview Available at https://bit.ly/32JeiLY and ACOSS (2022), Covid, inequality and poverty in 2020 & 2021: How poverty and inequality were reduced in the COVID recession and increased during the recovery: Build back better report 3 Available at https://bit.ly/3LWJtJn. It is a companion piece to our recent report on income inequality and poverty in the pandemic. In the absence of up-to-date statistics on the distribution of wealth, we project the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2017-18 wealth distribution forward to December 2021 using subsequent data on growth in the total value of different household assets, such as housing and superannuation.

Work, and inequality of wealth, matters

Wealth inequality is a controversial topic: some worry that it is excessive, others say we have the wealth we deserve. Yet it matters when people have too much or too little.

People who do not have enough wealth are living from week to week – if they lose their income through redundancy, illness, or a government decision to cut their social security payments, they have nothing to fall back on. The main form of household wealth in Australia is the home, and those who don’t own their home face a much greater risk of losing their shelter.

On the other hand, if a minority of people hold too great a share of a nation’s wealth, that can give rise to self-perpetuating inequalities in living standards, political power and influence.2Picketty T (2015), The Economics of Inequality. Belknap Press. https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674504806

Australians are the fourth-richest people in the world, on average

According to Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Report,3Credit Suisse (2021), Global wealth report 2021 Available at https://www.credit-suisse.com/media/assets/corporate/docs/about-us/research/publications/global-wealth-report-2021-en.pdf the average wealth of Australian households was $628,000 per adult in 2020, the fourth highest in the world behind Switzerland, the United States and Hong Kong:

- A relatively high proportion of wealth in Australia (58%) is in non-financial assets – mainly housing – compared with a global average of 46%.

But many people are financially vulnerable because they have low financial buffers or high debts

In 2018, 29% of low-income households (the lowest 40% ranked by income) were ‘over-indebted’ with debt over 3 times annual income:

- This was the sixth-highest incidence of risky debt among the 23 wealthy nations surveyed.

In that year, 39% of low-income households lacked enough liquid assets to cover 3 weeks of lost income:

- During the pandemic-induced recession in 2020 the Coronavirus Supplement and JobKeeper payments shielded many from financial hardship, but the safety net is much weaker now and living costs are rising.

Despite the 2020 recession, overall household wealth grew as much over the last 3 years as the previous 15

Average household wealth rose (after accounting for inflation) by $341,000 over the 3 years from 2018 to 2021, compared with an increase of $327,000 over the 15 years from 2003 to 2018.4Unless otherwise indicated, all wealth estimates are adjusted for inflation to 2019-20 dollars per household or person and take account of related debt.

- After declining by 3% in the March quarter 2020 at the onset of recession, average household wealth rose by 12% to December 2020, then by an extraordinary 26% to December 2021.

- On average, it rose by 11% per year (after inflation) from 2018 to 2021, compared with 3% per year from 2003 to 2018. Among the main drivers were historically low interest rates and high levels of household saving due to COVID restrictions and payments.

- The pace of growth in household wealth has slowed since December 2021 (beyond the scope of this report), in part due to increases in interest rates and expectations of more to come. Rising consumer price inflation will also moderate growth in the real value of household wealth.

Most of the increase in wealth since the pandemic began was in housing

Over two-thirds (69%) of the overall increase in household wealth during the pandemic was in residential property, which rose in value by 22% through the year to December 2021 – the highest annual increase in 35 years. This followed an increase of 3% through 2020 despite the recession.

The total value of residential property in Australia exceeded $10 trillion (million million) for the first time in March 2022.

This shifted the balance of wealth towards property and away from financial assets. The 3 largest contributors to the overall increase in household wealth from December 2018 to December 2021 were:

- Owner-occupied housing, which contributed 55% of the increase;

- Investment property, contributing 14%; and

- Superannuation, which contributed 16%.

Household wealth is still shared very unequally

Consistent with the findings of our last Inequality in Australia report (which used 2017-18 data), wealth is still very unequally distributed in 2021-225 We rely on wealth data for the first half of 2021-22 (July to December 2021) for these estimates:

- The highest 10% of households by wealth (the ‘richest’) has an average of $6.1 million in assets, or 46% of all wealth.

- The next 30% (the ‘comfortable middle’) have an average of $1.7 million in assets, or 38% of all wealth.

- That leaves the majority – the lower 60% – with an average of $376,000 in assets, or just 17% of all wealth.

Wealth inequality rose sharply from 2003 to 2018, then declined modestly in the pandemic

During the sustained period of economic growth from 2003-04 to 2018-19, wealth inequality increased sharply:

- The wealth of the highest 10% of households rose by an average of $1.9 million or 65%.

- That of the middle 30% rose by an average of $380,000 or 44%.

- That of the lower 60% rose by an average of $45,000 or 20%6After adjustment for inflation.

In the first 2 years of the pandemic (during 2019-20 and 2020-21, including the recession), wealth inequality declined slightly:

- The wealth of the highest 10% of households rose by an average of $530,000 or 11%.

- That of the middle 30% rose by an average of $168,000 or 13%.

- That of the lower 60% rose by an average of $43,000 or 16%.

In the third year of the pandemic (2021-22, a year of economic recovery), wealth inequality declined further:

- The wealth of the highest 10% of households rose by an average of $900,000 or 17%.

- That of the middle 30% rose by an average of $276,000 or 20%.

- That of the lower 60% rose by an average of $66,000 or 21%.

The Gini coefficient for household wealth rose from 0.57 in 2003-04 to 0.62 in 2018-19, then declined to 0.61 in 2021-22.7The Gini coefficient is a measure of inequality in which complete equality has a value of 0 and complete inequality has a value of 1.0.

The richest 10% still hold almost half, and the richest 1% one-seventh of all household wealth

In 2021, the richest 10% held:

- 46% of all wealth, compared with 47% in 2018 and 42% in 2003;

- 4 times the average wealth of the middle 30% and 16 times that of the lower 60%.

In 2021, the richest 1% held:

- 14% of all wealth, compared with 15% in 2018 and 12% in 2003;

- 11 times the average wealth of the middle 30% and 50 times that of the lower 60%.

The average wealth of Australia’s 131 billionaires is $3.6 billion, up 12% from last year

The 131 billionaires hold 3% of all wealth, approximately equal to that of the lowest 30% of households ranked by wealth, even though they are just 0.0005% of the adult population.8Their share of all household (as distinct from personal) wealth may be higher, as many billionaires are partnered with other billionaires. A billion dollars is a thousand million dollars.9The Australian Business Review: Australia’s richest 250. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/australias-richest-250#newscorpau_custom_html-14

Through 2021 their wealth increased by an average of $395 million or 12%, somewhat below the 16% increase for the highest 1% of households.10Note that the increase for the highest 1% was measured from the second half of 2020 to the second half of 2021.

-

The pace of growth in their wealth varied according to the industry in which they invested. Miners and property developers fared better than manufacturers and retailers, for example.

Rising home prices moderated overall wealth inequality….

From 2018 to 2022, the share of overall wealth held in owner-occupied homes rose from 37% to 41%.

The dominance of housing in wealth accumulation moderated overall wealth inequality because owner-occupied housing is relatively concentrated in the middle 30% of the wealth distribution:

- In 2021, the middle 30% held 46% of owner-occupied housing wealth, compared with 39% of superannuation, and just 14% of shares and 15% of own-business assets.

- In contrast, the richest 10% held 35% of owner-occupied housing, 42% of superannuation, 84% of shares and 82% of own-business assets.

…but shut younger people and those with low incomes out of secure, affordable housing

There is a big downside to rapid growth in home prices. Unlike other assets, housing provides shelter for people and their families. By treating it as an investment, we have locked many younger people and those with low and modest incomes out of secure, affordable homes.

As a proportion of the average household’s owner-occupied housing assets (minus related debt):

- The value of those held by people under 35 years fell from 31% in 2003 to 26% in 2021;

- That of people 35-44 years fell from 82% in 2003 to 69%;

- That of people over 64 rose from 140% in 2003 to 144%.11These average values include people in households with zero own-home wealth (e.g. renters), who are more likely to be younger.

Over the period from 2003 to 2021:

- Home ownership among people aged 25 to 29 years fell from 44% to 38% and among people aged 30-34 it fell from 57% to 50%;

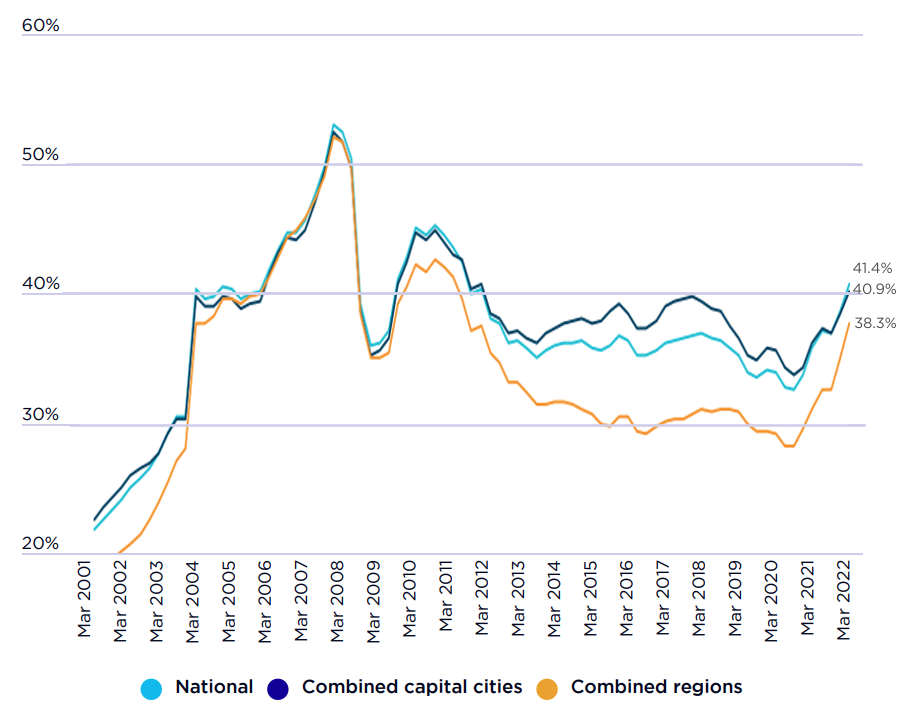

- The proportion of median household disposable income required to service a typical home mortgage rose from 27% to 41%;

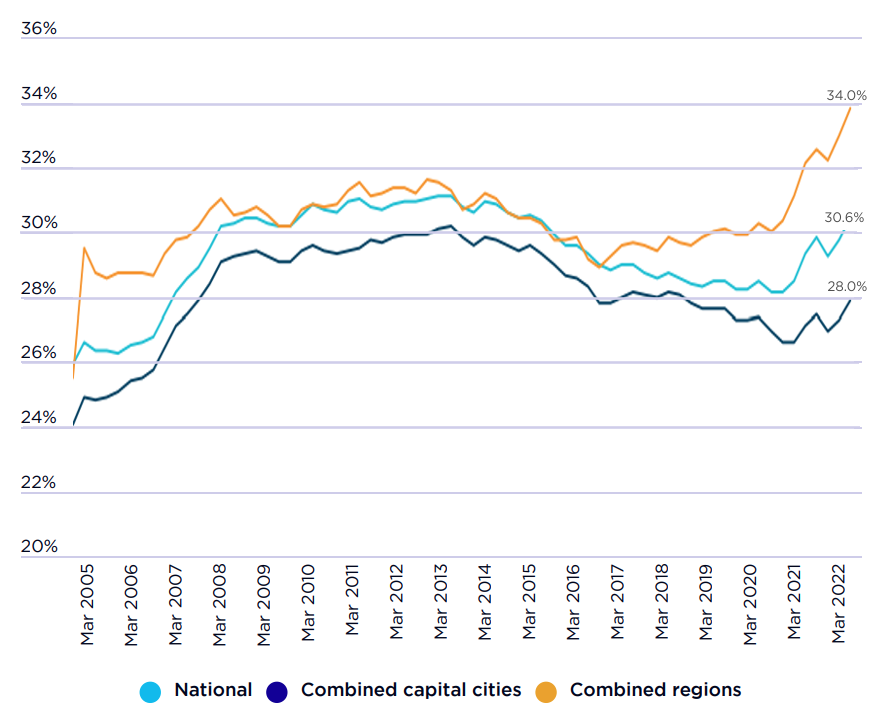

- The proportion of median household disposable income required to pay the median rent rose from 26% to 31%.

Out of almost 50,000 rental listings surveyed by Anglicare Australia in May 2022, only 7 were affordable (costing less than 30% of income) for a single adult on Jobseeker Payment and just 9 were affordable for a single parent on Jobseeker Payment with one child.12Anglicare Australia (2021), Rental Affordability Snapshot 2022. https://www.anglicare.asn.au/publications/rental-affordability-snapshot-2022/

This infographic compares the wealth holdings of the richest 10% of households ranked by wealth with the next 30% and lower 60%.

Half of all wealth is owned by the richest 10%

We divide households in this way because wealth is strongly skewed towards the richest.

In 2021, the richest 10% held 46% of all household wealth (the richest 1% alone had 14%).

The next 30%, whom we call the ‘comfortable middle’ (noting however that they are in the top half of the distribution) had 38% of all household wealth, leaving the remaining 60% with 17%.

A profile of wealth in 2021

NOTE: Households are ranked by wealth, not income. Average wealth is minus related debt (e.g. home mortgages), with remaining debt classified as ‘other debt’. For method used see Attachment 3 below.

The ‘comfortable middle’ corresponds broadly to the ‘medium’ definition of ‘middle class’ in Wilkins et al (2020); that is, those with between 50% and 150% of the median wealth level. In 2018, that group comprised 32% of households ranked by wealth (Wilkins R et al (2020), The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 18. Melbourne Institute).

Values are adjusted for inflation to 2019-20 dollars. ‘Other non-financial assets’ = consumer durables such as cars.

Purpose of this report

This report is part of a series on poverty and inequality in Australia produced by a partnership between the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) and UNSW Sydney.

Previous reports have used the biennial ABS Income and Housing Surveys to measure the extent of income and wealth inequality and poverty, examine their main causes and groups impacted, and to track trends in inequality and poverty.

The COVID recession and public policy responses in Australia since 2020 have dramatically impacted household incomes and wealth. Large shifts in incomes and wealth that would normally take decades to play out have been compressed into the last 3 years.

This report examines changes in how wealth is distributed among households between 2018-19 and 2021-22, which includes the COVID recession and recovery. To update estimates of wealth held in different forms (such as owner-occupied housing and shares) by wealthier and poorer households, we project wealth estimates from the 2017-18 ABS Survey and Income and Wealth forwards to December 2021, using subsequent data on growth in the total value of different forms of wealth (see Attachment 3).

We aim to answer the following questions:

- How was overall household wealth impacted by the COVID recession and recovery, and how did this compare with growth in wealth over the longer-term?

- How did the distribution of household wealth change over this period, including changes in average wealth across the distribution and changes in the shares of wealth held in different assets (such as housing and shares)? How did this compare with longer-term trends?

- What happened during this period to overall wealth levels at the top of the distribution – the highest 10% and 1% and the small minority of billionaires?

- How does the overall level of household wealth and its distribution in Australia compare internationally?

- What are the implications of growth in housing prices for affordability?

Attachment 1 provides international comparisons, Attachment 2 summarises the main economic and policy influences on the trends in household wealth observed in this report, and Attachment 3 outlines the methods we used to estimate the wealth distribution for the most recent years.

This report updates the more comprehensive analysis of wealth inequality in the following reports produced by the Partnership:

- Davidson P, Bradbury B, Wong M & Hill T (2020), Inequality in Australia 2020: Overview ACOSS & UNSW Sydney

- Davidson P; Bradbury B; Wong M & B; Hill P (2020), Inequality in Australia 2020: Who is affected and why? ACOSS & UNSW Sydney

It complements the following more recent reports in our Build Back Fairer series:

- Davidson, P (2022), A tale of two pandemics: COVID, inequality and poverty Build back fairer, report 3, ACOSS & UNSW Sydney

- Bradbury, B and Hill, T (2021), Australian income support since 2000. Build back fairer, report 2, ACOSS & UNSW Sydney

1.Trends in overall wealth

Australians are the fourth-richest people in the world, on average…

According to Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Report, the average wealth of Australian households was $628,000 per adult in 2020, the fourth highest in the world behind Switzerland, the United States and Hong Kong (Figure 1.1). Note that the figure below includes regions, such as North America and Europe, as well as individual countries.

Figure 1.1 Average wealth per adult in 2020 ($AUS)

…but we have a major problem with household debt

Due to our high and rapidly growing home prices and relatively easy access to credit, Australian households are more indebted than in most other wealthy nations. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) regards households in the lowest 40% by income with debt at least 3 times their annual disposable income as ‘over-indebted’ and therefore at risk financially:

- Australia ranks 6th highest on this measure among 23 OECD countries, with 29% of low-income households over-indebted (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Share of indebted households with debt-to-annual income ratio above 3 (% in 2017-19)

In 2018, 39% of low-income households in Australia lacked enough liquid assets to cover 3 weeks of lost income.13OECD (2021), Inequalities in household wealth and financial insecurity of households, OECD Policy Insight.

- During the 2020 recession the Coronavirus Supplement and JobKeeper payments shielded many from financial hardship but the income support safety net is much weaker now after the withdrawal of these supports.14Davidson P (2022), op cit

Despite the 2020 recession, overall household wealth grew almost as much over the last 3 years as it did over the previous 15

The COVID-19 pandemic ushered in a turbulent period of financial shocks and adjustments, including a deep recession in the June quarter of 2020, an unprecedented household income support package in response, and a rapid recovery when lockdowns were eased. This had major impacts on household wealth as the values of assets such as shares and housing at first fell then quickly recovered off the back of forced saving by wealthier households (who were unable to travel and eat out, for example) and historically low interest rates. Trends in key asset markets are examined in more depth in Attachment 2.

Since the recovery had a far greater impact on asset values than the recession, average household wealth rose by $341,000 over the 3 years from 2018 to 2021 after adjusting for inflation, compared with an increase of $327,000 over the 15 years from 2003 to 2018.15Unless otherwise indicated, all wealth estimates are adjusted for inflation to 2019-20 dollars per household or person and take account of related debt. We refer to inflation-adjusted wealth as ‘real’ wealth. The trend analysis begins in 2003, the earliest available data from the ABS.

- After declining by 3% in the March quarter 2020 (at the onset of recession), average household wealth rose by 12% to December 2020, then by an extraordinary 26% to December 2021.

- On average, it rose by 11% per year after inflation from 2018 to 2021, compared with just 3% per year from 2003 to 2018.

Figure 1.3 shows the longer-term trend in household wealth per capita since 2000 (per person rather than household so the numbers are lower than in our distributional analysis), adjusted for inflation:

- From 2000 to the Global Financial Crisis in 2009, it grew from $257,000 to $353,000 (5% a year);

- After a slight dip in 2009, it grew at a slower pace (2% per year) to reach $413,000 in 2018;

- From 2018 to 2021, despite the recession it grew by 11% a year to $544,000.

Figure 1.3: Household wealth per capita (2019 dollars)

The pace of growth in household wealth has slowed since December 2021 (beyond the scope of this report), in part due to increases in interest rates and expectations of more to come.16Reserve Bank of Australia (2022), Statement on Monetary Policy, May 2022

Most of the increase in wealth since the pandemic began was in housing

From December 2018 to December 2021 real net household wealth rose by 43% (Figure 1.4).17We refer to trends in inflation-adjusted wealth as ‘real’ wealth. ‘Net’ wealth is the value of assets adjusted for related debt.

Of this increase:

Over half (55% of the increase) came from owner-occupied housing (which comprised 37% of all wealth in 2018).

One-seventh (14%) came from investment property (11% of wealth in 2018).

One-sixth (16%) came from superannuation (22% of all wealth in 2018).

The remaining 15% of the increase in overall wealth came in roughly equal measure from shares bonds and trusts, bank deposits, business assets, and household durables18Furniture, electronic items, artworks, for example. (which together comprised 30% of all wealth in 2018).19Disproportionate growth in housing wealth during the recovery from the COVID recession appears to be a common experience in wealthy nations. See Muellbauer J (2022), Real estate booms and busts: Implications for monetary and macroprudential policy in Europe. European Central Bank Forum of Central Banking, Sintra 27-29 June 2022.

Figure 1.4: Increase in real net household wealth per capita (as a % of overall wealth in December 2018)

Dwelling prices rose by $76,000 per person or 22% through the year to December 2021 – the highest annual increase in 35 years. This followed an increase of $23,000 per person or 3% through 2020 despite the recession.20Corelogic (2022), Hedonic Home Value Index. The total value of residential dwellings in Australia exceeded $10 trillion (million million) for the first time in March 2022, rising $1.8 trillion over the previous past 12 months.21ABS (2022), Total Value of Dwellings (Cat 6432.0).

This has implications for wealth inequality since, as discussed later, each of these asset types are distributed differently among households.

The spike in home prices since mid-2020 can be attributed to low interest rates, a build-up of savings by people on higher incomes during lockdowns, and government housing subsidies

Attachment 2 outlines the main drivers of rapid growth in household wealth, including in housing, from the recession in mid-2020 through to December 2021. A recent report in our COVID-19 housing & homelessness impacts series identified the following contributing factors to inflation in housing prices:

- A reduction in the Reserve Bank cash rate target to an historic low of 0.1% through 2021, which prompted a reduction in new home loan interest rates from an average of 3.3% in January 2020 to 2.6% in December 2021;

- COVID income supports and restrictions, which lifted incomes (mainly for low and middle-income households) and reduced expenditures (especially for higher-income households, for example on meals out and recreational travel), more than doubling average saving levels from $806 per person over the year to December 2019 to $1,722 over the year to December 2021;

- New government subsidies for first home buyers and for people building or renovating homes (Homebuilder scheme); and

- Behavioural changes in response to lockdowns including working from home (giving rise to a preference for larger better-equipped homes) and migration from cities into regional areas (where home prices and rents rose most sharply).22RBA Statistics (2022), Household & Business Balance Sheets, Current prices, Table E1; ABS (2022), Consumer Price Index; Pawson H, Martin C, Aminpour F, Gibb K, Foye C (2022), COVID-19: Housing market impacts and housing policy responses – an international review ACOSS/UNSW Sydney Poverty and Inequality Partnership Report No. 16, Sydney; Reserve Bank of Australia (2022), Owner occupier variable housing rates (for new loans).

2.Trends in overall wealth inequality

Household wealth is still shared very unequally

Consistent with the findings of our last Inequality in Australia report, wealth is still very unequally distributed in 2021-22 (Figures 2.1 and 2.2)23Davidson P, Bradbury B, Wong M & Hill T (2020), Inequality in Australia, Part 1: Overview.ACOSS & UNSW Sydney.. We rely on wealth data for the first half of 2021-22 (July to December 2021) for these estimates.:

- The highest 10% of households by wealth has an average of $6.1 million or 46% of all wealth.

- The next 30% have an average of $1.7 million or 38% of all wealth.

- That leaves the majority – the lower 60% – with $376,000 or just 17% of all wealth.

Figure 2.1: Average wealth by wealth group (2019 dollars per household)

Figure 2.2: Average wealth by wealth group (%)

The sustained period of economic growth from 2003 to 2018 disproportionately benefited the richest, then wealth inequality moderated in the pandemic

During the sustained period of economic growth from 2003-04 to 2018-19, wealth inequality increased sharply (Figure 2.3):

- The wealth of the highest 1% of households rose (after inflation) by an average of $6.8 million or 84%;

- The wealth of the highest 10% rose by an average of $1.9 million or 65%;

- That of the middle 30% rose by an average of $380,000 or 44%; and

- That of the lower 60% rose by just $45,000 or 20%.

In the first 2 years of the pandemic (during 2019-20 and 2020-21 including the recession), wealth inequality declined slightly:

- The wealth of the highest 1% of households rose by an average of $1.5 million or 10%;

- The wealth of the highest 10% rose by an average of $530,000 or 11%;

- That of the middle 30% rose by an average of $168,000 or 13%; and

- That of the lower 60% rose by an average of $43,000 or 16%.

In the third year of the pandemic (2021-22, a year of economic recovery), wealth inequality declined further:

- The wealth of the highest 1% of households rose by an average of $2.5 million or 16%;

- The wealth of the highest 10% rose by an average of $900,000 or 17%;

- That of the middle 30% rose by an average of $276,000 or 20%; and

- That of the lower 60% rose by an average of $66,000 or 21%.

Figure 2.3a: Increase in wealth, by wealth group since 2003 (2019 dollars per household)

Figure 2.3b: Increase in wealth, by wealth group since 2003 (%)

The shares of wealth held by different groups diverged during the sustained period of economic growth, then became somewhat less unequal after 2018

In 2003, wealth was shared very unequally (Figure 2.4):

- The highest 10% had 42% of all wealth, the middle 30% had 38% and the lower 60% had 20%.

By 2018, the distribution was skewed even further towards the richest:

- The highest 10% had 47% of all wealth, the middle 30% had 37% and the lower 60% had 16%.

During the COVID recession and recovery, wealth inequality moderated somewhat but wealth was still distributed more unequally than in 2003:

- By 2021, the highest 10% had 46% of all wealth, the middle 30% had 38% and the lower 60% had 17%.

Figure 2.4: Changes in the distribution of wealth since 2003 (% share of all wealth)

Overall wealth inequality grew with economic growth (2003-18) then moderated in the pandemic (2018-21) but remained higher than in 2003.

Figure 2.5 shows trends in a summary measure of inequality, the ‘Gini coefficient’. The Gini varies across a range from zero (equal wealth) to one (where all wealth is held by a single household):

- It rose sharply from 0.573 in 2003 to 0.624 in 2018;

- Then declined slightly to 0.613 by 2021, close to the level reached around 2016.

Figure 2.5: Wealth inequality (Gini coefficient)

Avoiding a ‘K-shaped’ recovery‘When I took office, one of my greatest concerns was a ‘K-shaped recovery’ from the pandemic; a recovery where high-income households rebounded quickly – or even emerged better-off – while low- and middle-income families suffered for a very long time. We can be confident now that’s not going to happen, thanks in part to your support of the fiscal stimulus in the American Rescue Plan.’ US Treasury Secretary Yellen.24Yellen J (2021), Testimony to the Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, U.S. House of Representatives, 10 June 2021, United States Department of The Treasury. As we found in our own assessment of the impact of COVID on income inequality and poverty, the Australian government’s income support measures and wage subsidies prevented a rise in income inequality and poverty during the COVID recession, but poverty rose again to a higher level than before when the extra income supports were removed. Public income supports and low interest rates also boosted household wealth, as this report shows.25Davidson, P., (2022) COVID, inequality and poverty in 2020 and 2021. ACOSS/UNSW Sydney Poverty and Inequality Partnership, Build Back Fairer Series, Report No. 3, Sydney. |

|---|

3.Trends in wealth inequality by asset type

Rising home values (relative to other assets) are likely to dampen overall wealth inequality

From 2018 to 2022, the share of overall wealth held in owner-occupied homes rose from 37% to 41%.

The predominance of owner-occupied housing in wealth accumulation through the pandemic moderated overall wealth inequality because owner-occupied housing is relatively concentrated in the middle 30% of the wealth distribution (Figure 3.1):

- In 2021, the middle 30% held 46% of owner-occupied housing wealth, compared with 39% of superannuation, 26% of investment property, and just 14% of shares and 15% of own-business assets.

- In contrast, the richest 10% held 35% of owner-occupied housing, 42% of superannuation, 68% of investment property, 84% of shares and 82% of own-business assets.

Figure 3.1: Shares of all wealth by asset type held by each wealth group (% of wealth in 2021)

| Because housing wealth tends to be less unequally distributed than financial wealth, it can be argued that higher house prices reduce overall wealth inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient. However, they have widened the gap between owners and non-owners, between older and younger generations, and inequality within younger cohorts, within which the rate of owner-occupation has recently been falling in countries with the highest increases in house price to income ratios. |

|---|

Muellbauer J (2022), Real estate booms and busts: Implications for monetary and macroprudential policy in Europe. European Central Bank Forum of Central Banking, Sintra 27-29 June 2022, p57.

The richest hold more of their wealth in shares, bonds, trusts, own business assets and investment property, while those with less wealth rely more on their homes, superannuation, bank deposits and household durables

Of the wealth of the richest 10% in 2021 (Figure 3.2):

- A higher proportion was held in investment property (18%), shares, bonds and trusts (13%), and own-business assets (9%), compared with 8%, 3% and 2% respectively for the middle 30%;

- A lower proportion was held in their homes (32%), superannuation (19%), deposits (5%), and durables (4%), compared with 50%, 21% and 9% respectively for the middle 30%.26Of course, the average value of assets held by the richest 10% are generally much higher than for people with less overall wealth.

Wealthier people, having met their basic needs (such as housing and consumer durables) and set aside readily accessible funds for regular living costs (for example in bank deposits), tend to invest more in assets with higher returns (such as shares, bonds and trusts). People with less wealth or lower incomes have less scope to invest in those higher yielding assets, except through compulsory saving in superannuation. This is one of the reasons that wealth inequality grows over time.

On the other hand, investments with higher returns are often riskier. For this reason, wealth inequality may decline in recessions (when the value of riskier investments such as shares often falls sharply).

Of the wealth of the lower 60% in 2021:

- Higher proportions were held in superannuation (23%), durables (17%) and deposits (8%), compared with 21%, 9% and 7% respectively for the middle 30%;

- A similar proportion was held in their homes (48% compared with 50%, taking account of people who were not owner-occupiers); and

- Almost negligible proportions were held in investment property (4%), shares, bonds and trusts (1%), and own-business assets (1%), compared with 8%, 3% and 2% respectively for the middle 30%.

In part, this reflects the relative youth of people with low levels of wealth. Young people are less likely to be homeowners, and more of their wealth is tied up in bank deposits and cars.

Figure 3.2: Profile of wealth of each wealth group (% of all wealth in 2021)

The contribution of each asset type to overall wealth inequality is a product of the concentration (degree of inequality) of wealth held in that asset and the share of all wealth in that form

The Gini coefficient shown in Figure 2.5 is a product of the degree of concentration (inequality) in the distribution of each asset type and the share of each asset type in overall wealth. For example, an asset type may be heavily concentrated in the hands of the highest 10% of households ranked by overall wealth, but this will have less impact on overall inequality if it represents only a small share of overall wealth.

Figure 3.3 shows trends in a measure of the concentration (inequality) of wealth within each asset type since the beginning of the pandemic. In 2018, this ‘concentration coefficient’, which has a value between zero (complete equality) and one (complete inequality) was:

-

Relatively high for shares, bonds and trusts (0.89), own business assets (0.89), and investment property (0.79); and

-

Relatively low for owner-occupied homes (0.57), superannuation (0.57), deposits (0.55) and durables (0.34).

There were slight variations in these ‘concentration coefficients’ between 2018 and 2021, for example the distribution of owner-occupied housing became slightly less concentrated (0.57 to 0.56)27Note that the method used to update our estimates for wealth distribution from 2017 to 2021 assumes that the distribution of wealth within each asset type (as distinct from the distribution of that asset across overall household wealth groups) remained constant (since we lack up-to-date data on the distribution of wealth as distinct from its overall value by asset type). It is possible that the concentration of wealth held in different assets changed more than indicated here..

Over the same period, as noted in our earlier analysis, there were substantial changes in the share of overall wealth held in different assets:

- The share held in owner-occupied housing rose from 0.37 to 0.41 (from 37% to 41%);

- The share held in investment property rose from 0.11 to 0.12; and

- The share held in most other assets declined accordingly.

This is another way to show how, all things equal, the increased share of wealth held in owner-occupied housing, which was already high in 2018, reduced wealth inequality.

Figure 3.3: Concentration and share of overall wealth by asset type, 2018-2021

4. The downside of higher home values

Unlike other assets, housing provides shelter, and young people and those on low incomes are missing out

By treating housing as an investment, we have locked many younger people and those with low and modest incomes out of secure, affordable homes.

Figure 4.1 shows that wealth inequality has increased across generations since 2003, especially in the distribution of owner-occupied housing. As a proportion of the average value of owner-occupied homes held across all age groups:

- The average value held in households with a reference person (a category defined by the ABS which broadly refers to the highest income-earner in a household) under 35 years fell from 31% in 2003 to 26% in 2021;

- That of those aged 35-44 years fell from 82% in 2003 to 69%;

- That of those aged 64 years rose from 140% in 2003 to 144%.28These average values include people in households with zero own-home wealth (e.g. renters), who are more likely to be younger. They take account of mortgage debt, noting that older people are less likely have this.

Figure 4.1: Average wealth of households by age, as a % of average wealth of all (%)

While not all older people hold substantial wealth in their homes (16% of people aged 65-74 rent), large increases in home values disproportionately benefit those who have owned their homes for a long time at the expense of younger people locked out of the market. From 2003 to 2021, home ownership among people aged 25 to 29 fell from 44% to 38% and among people aged 30-34 it fell from 57% to 50%.29ABS (2022), Housing Occupancy and Costs Australia, 2019-20. See Attachment 2 for more details.

Higher rents and mortgage payments put people on low and modest incomes under increasing financial stress

Government policies introduced during lockdowns in 2020 and 2021, including income supports and eviction moratoria, improved the security and affordability of housing. However, a return to ‘normal’ settings and sharp increases in home values have put people on low and modest incomes under increasing pressure. Rents have risen by an average of 20% in regional areas and 14% in cities over the last 2 years.30Pawson H et al (2021), op cit.

Disturbingly, of almost 50,000 rental listings surveyed by Anglicare Australia in May 2022 only 7 were affordable (costing less than 30% of income) for a single adult on Jobseeker Payment and just 9 were affordable for a single parent on Jobseeker Payment with one child.31Anglicare Australia (2022), op cit.

Figure 4.2 shows that, from 2003 to 2021:

- The proportion of median household disposable income required to service a typical home mortgage rose from 27% to 41%;

- The proportion of median household disposable income required to pay the median rent rose from 26% to 31%.

Figure 4.2(a): Proportion of median income required to pay a typical mortgage on a recently purchased home (%)

Note: Assumes owner has borrowed 80% of median dwelling value and is paying the average discounted

variable mortgage for a term of 25 years. Percentage of median gross annual household income required to

pay median rent on a new lease

Figure 4.2(b): Proportion of median income required to pay the median rent (%)

5. The wealth of Australia’s 131 billionaires

Australia’s 131 billionaires have average wealth of $3.6 billion each

According to The Australian newspaper, in 2021 there were 131 billionaires (with wealth over a thousand million dollars) in Australia.32The Australian Business Review: Australia’s richest 250. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/australias-richest-250#newscorpau_custom_html-14 Note that not all of the 250 surveyed were billionaires.

Between early 2020 and early 2021, when adjusted for inflation to 2019 values:

- Their average wealth rose by 12% from $3,169 million to $3,574 million (Figure 5.1);

- Their overall wealth rose from $416 billion to $468 billion.

Their average wealth grew by 12% between 2020 and 2021, after adjusting for inflation

The pace of growth in their wealth varied according to the industry in which they invested. Some saw their wealth decline during the pandemic due to their industry’s exposure to COVID lockdowns or the fall in share values in the recession. Others profited from lockdowns and government business support or from the subsequent boom in asset markets:

- Generally, miners and property developers fared better than manufacturers and retailers.

Figure 5.1: Average wealth of 131 billionaires compared with the highest 1% of households ($)

Over a similar period (between 2020-21 and the first half of 2021-22) the average wealth of the top 1% of households ranked by wealth rose by 16% from $16 million to $19 million, after adjusting for inflation (Figure 5.1).

The 131 billionaires hold almost as much wealth as the lower 2.8 million households, ranked by wealth

The 131 billionaires comprised 0.001% of the population yet held 2.9% of all household wealth in 2021, a decline from 3% in 2020. Figure 5.2 shows that they held more wealth among them than the lower 20% of households ranked by wealth (who held 0.7% of all wealth) and somewhat less than the second-lowest 20% (with 4.7%):

- This suggests that 131 individuals held almost as much wealth between them as the 2.8 million households in the lowest 30% ranked by wealth.33If, for example, the lower half of the second 20% held one third of the wealth of that group, their share of all wealth would be 2.35%. If we add this to the 0.7% share of the lowest 20%, then the lowest 30% would have 3.05% of all wealth.

Figure 5.2: Share of all wealth held by 131 billionaires compared with low-wealth groups (%)

Attachment 1: International comparison

Australia’s wealth profile is skewed towards non-financial assets, mainly housing

A relatively high proportion of household wealth in Australia (58%) is in non-financial assets – mainly housing – compared with a global average of 46% (Figure A1.1).

Figure A1.1: Profile of household wealth in different countries in 2020 (% of all wealth)

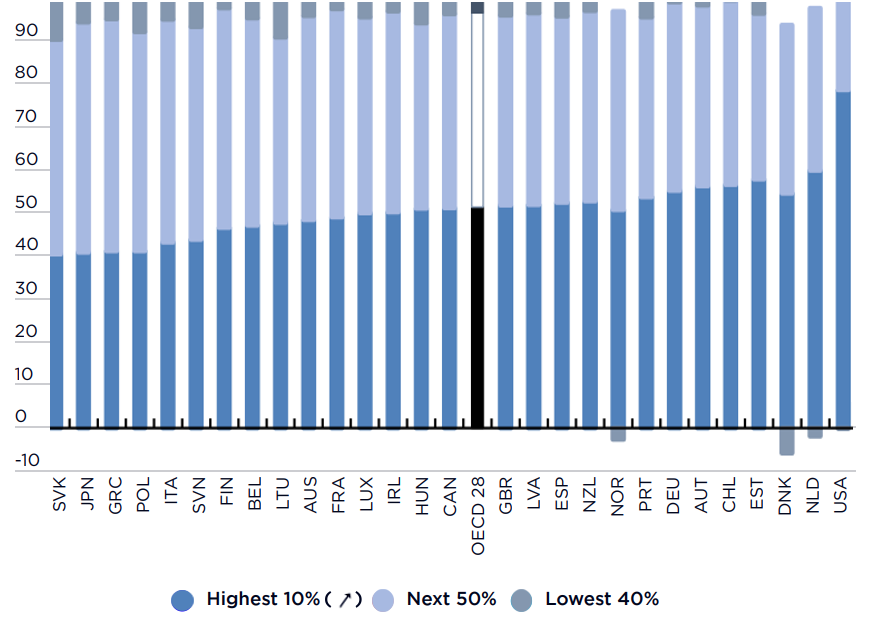

Wealth is distributed somewhat less unequally in Australia than in other wealthy nations

The level of wealth inequality in Australia around 2018 (before the pandemic) was somewhat below the average among 28 wealthy nations surveyed by the OECD (Figure A1.2):

- The highest 10% of households ranked by wealth held approximately 45% of all wealth in Australia compared with an OECD average of approximately 50%.

The high level of home ownership and housing wealth in Australia is a major reason for this.

Figure A1.2: Shares of overall wealth held by the lowest 40%, middle 50% and highest 10% around 2018 (%)

Attachment 2: Factors impacting household wealth and wealth inequality in the pandemic

While the COVID recession in March 2020 at first reduced household wealth through declines in share and housing prices, a combination of lockdowns, public income support, and low interest rates dramatically lifted household saving and wealth from mid-2020 through to December 2021. The largest contributor to this increase in wealth was a sharp rise in housing prices (Figure A2.1).

Figure A2.1: Household wealth per capita (in 2019 dollars)

Interest rates were reduced to historic lows to ward off the COVID recession

In April 2020 the Reserve Bank reduced its cash rate target to an historic low of 0.1% (Figure A2.2). Consequently, typical interest rates for new home loans fell to 2-3%. These and other interest rate reductions boosted investment in housing, increasing demand and putting strong upward pressure on house prices and housing wealth.

Figure A2.2: Interest rates from 2019 to 2021 (% per annum)

Government income support and COVID lockdowns boosted household saving

As outlined in our previous report on the impact of COVID on income inequality and poverty, public income supports such as JobKeeper Payment and the Coronavirus Supplement boosted the incomes of many low-income households while COVID restrictions reduced spending on such items as holidays, entertainment and eating out.34Davidson P (2022), op cit. The result was a sharp increase in overall household saving (Figure A2.3).

Figure A2.3: Net saving per capita (in 2019 dollars)

Higher-income households saved the most

People with higher incomes have more capacity to save, while those with low incomes must often spend all their income or more to meet current needs. This contributes to increases in wealth inequality over time, to the extent that income and wealth inequality are correlated.

Between 2020 and 2021, the rate of saving by the highest 20% of households ranked by income rose by half (from 8% to 12% of disposable income), along with that of the middle 20% (from 2% to 3%). The average saving rate for the lowest 20% was less than 1% throughout this period (Figure A2.4).

Figure A2.4: Gross household saving by income quintile (% of aggregate annual household disposable income)

Home prices rose sharply after the recession

Average capital city home purchase prices rose by 3% through 2020 despite dipping slightly in the recession, then by 22% the following year to finish 24% above September 2017 values (Figure A2.5).35Corelogic (2022), Hedonic home value index. https://eliteagent.com/two-speed-market-as-capital-city-price-growth-diverges/

Figure A2.5: Cumulative increase in capital city dwelling prices from September 2017 to December 2021 (%)

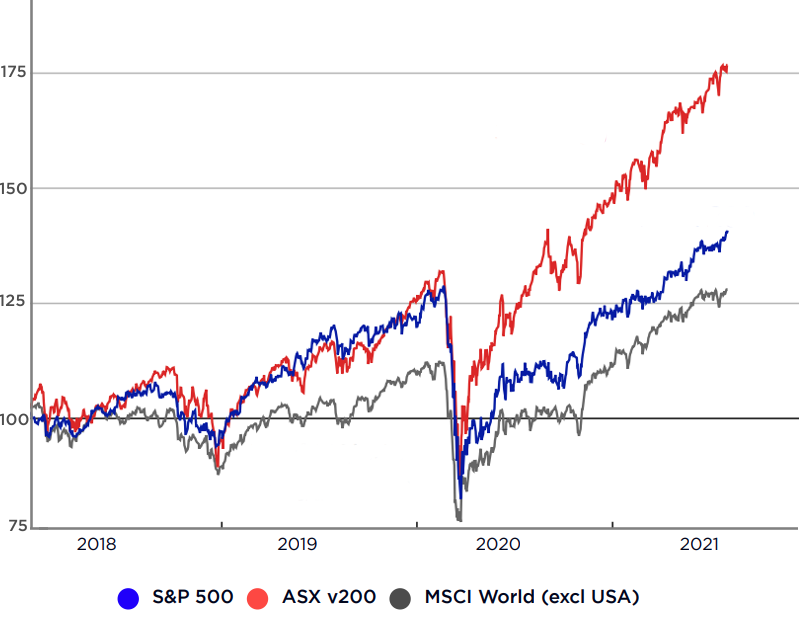

Share prices declined in the recession, then rose strongly

Share prices in Australia and other countries in which Australians invest responded quickly to the recession, falling sharply. Over the following year they grew strongly – to end well above their average values from the beginning of 2020: (Figure A2.6).

- For example, the Australian Securities Exchange index (ASX) fell by 21% of its January 2020 value by April 2020 but was restored to just 6% below the January 2020 value by December of that year. By December 2021 it was 6% above its January 2020 value.

Figure A2.6: Total return indices

Superannuation investment returns followed a similar pattern to share and house prices

Superannuation account balances vary over time through a combination of net contributions (contributions minus any benefit payments) and investment returns. Since most superannuation funds invest in a combination of shares, bonds, property and cash deposits, their average investment returns broadly reflect returns on those investments.

As a proportion of their value in December 2019, superannuation account balances declined by 9% by March 2020 then rose to 18% above December 2019 levels by December 2021 (Figure A2.7).

Figure A2.7: Cumulative growth in superannuation assets (% of value in December 2019)

Attachment 3: Methods

To measure wealth inequality, we rely on the biennial Survey of Income and Housing produced by the ABS. The last 2 surveys were conducted in financial years 2017-18 (shortened here to ‘2017’) and 2019-20 (shortened to ‘2019’).

Projecting to 2021-22

The COVID downturn of 2020 and subsequent recovery had major impacts on household wealth and its distribution. The values of assets such as shares and housing fell in the downturn then recovered quickly as households increased their savings during lockdowns and interest rates fell to historically low levels. Since the latest ABS survey was conducted through 2019-20 it only covers the commencement of the downturn, not the subsequent recovery.

To assess the impact of both downturn and recovery on wealth inequality, we projected estimates of the wealth holdings of different household groups from the 2017 ABS survey forwards to December 2021 using available data on trends in overall household wealth by asset type (such as owner-occupied housing) published by the Reserve Bank of Australia (Table E01, December 2021 release). This table is derived from the ABS National Accounts series (ABS Cat. 5232.0 Australian National Accounts: Finance and Wealth). All results are reported in $2019-20 prices, inflated using the quarterly Consumer Price Index (CPI).

To obtain estimates of the distribution of household wealth in 2018-19 we inflated the values of each wealth component recorded in the 2017-18 survey by the per-capita growth in the matching wealth component (the average of the four-quarters of 2018-19 vs the four-quarters of 2017-18). Corresponding inflators are used for the other years, except that the 2021-22 estimate is based on the values for the December quarter 2021.

No other changes are made to take account of demographic, labour market or policy changes over the period. While our projection method takes account the impacts of these factors that might affect average wealth values, any other changes that have influenced the distribution of wealth are not reflected in our projections.

The table below indicates the RBA wealth category used to inflate each component of household wealth.

| Household survey wealth component | RBA wealth aggregate used for inflation |

| Own home | Household dwellings |

| Own home debt | Household total liabilities |

| Other real estate (net) | Household dwellings |

| Other non-financial assets | Household consumer durables |

| Superannuation | Household superannuation |

| Bank accounts | Household deposits |

| Shares, trusts, own-business, misc financial | Household equities |

| Investment loans, other debt | Household liabilities |

A key assumption underpinning these projections is that the distribution of the overall value of each asset type among household groups (ranked according to the value of that asset held by each group) remained constant. Because unit record data were not available for 2019 when we conducted our analysis, we used 2017 as the base year. This was the last ABS Income and Housing survey conducted before the COVID downturn and it was a more ‘normal’ year, before the turbulence of downturn and recovery.

The results for years prior to 2017 are based on the previous releases of the ABS Income and Housing Surveys.

We can compare our projections for 2019 with the published results from the survey conducted in that year. Our projection of average net household wealth is 0.9% lower than the ABS survey estimate. Our estimate of overall inequality (without any censoring of negative values) is 0.623, slightly higher than the ABS estimate of 0.611. These differences reflect both the limitations of the projection method, but also sampling and methodological variation in the surveys.

Asset types and household types

Household wealth consists of a range of assets including owner-occupied or investment housing, superannuation, financial assets such as shares and bank balances, and other non-financial assets such as cars. To report on household wealth, the current values of various assets held by a household are tallied, minus any debts owing (for example, home mortgages). Unlike our analysis of the distribution of income, the value of wealth holdings is not adjusted for household size (equivalised) to rank households by wealth.

Since wealth is generally shared within households (especially the home, if owner-occupied), the household rather than the individual is the unit of analysis. In addition to ranking households by wealth, we also report on the distribution of wealth among households in different age brackets (based on the age of the household reference person).

Measures of inequality

We use a range of measures of wealth inequality, including comparisons of the average wealth of different groups, each group’s share of overall wealth, and summary measures of inequality, the ‘Gini coefficient’ and ‘Concentration coefficient’. These coefficients vary across a range from zero (equal incomes) to one (where all income is held by a single household).

To work out the contribution made by different components of wealth (asset types such as owner-occupied housing and shares) to overall wealth inequality, we ‘decompose’ the Gini coefficient into these components. For each component, the contribution to the Gini coefficient is the product of its share of overall wealth and its concentration coefficient (a measure of inequality within that component). In other words, the contribution of an asset type to wealth inequality depends on its distribution across households with different total wealth levels, and its share of overall wealth.

ISSN: 1326 7124

ISBN: 978 0 85871 098 6

The wealth inequality pandemic: COVID and wealth inequality is published by the Australian Council of Social

Service, in partnership with UNSW Sydney.

Locked Bag 4777

Strawberry Hills, NSW 2012

Australia

Email: [email protected]

Website: http://povertyandinequality.acoss.org.au

© ACOSS and UNSW Sydney, 2022

This publication is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or

review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written

permission. Enquiries should be directed to the Publications Officer, Australian Council of Social Service.

Copies are available from the address above.

Suggested citation: Davidson, P. & Bradbury, B., (2022) The wealth inequality pandemic: COVID and wealth

inequality ACOSS/UNSW Sydney Poverty and Inequality Partnership, Build Back Fairer Series Report No. 4,

Sydney.

All images © istockphotos