Poverty in Australia 2023: Who is affected

Poverty in Australia 2023: Who is affected? is the latest report from the Poverty and Inequality Partnership between ACOSS and UNSW Sydney. It is the 20th report published by this Partnership.

This report uses data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) to identify the groups facing the highest risk of poverty; and the groups of people most likely to be living in poverty. It rounds out the story of poverty provided in our

previous Poverty in Australia report, Poverty in Australia 2022: A snapshot, which provided an overview of the numbers of people in poverty in Australia; and our most recent report Australian Experiences of Poverty, which took a

qualitative, experienced-focused approach to relate the experiences of people in poverty during 2020-21.

ACOSS and UNSW Sydney would like to thank those organisations who support this Partnership: 54 reasons (part of the Save the Children Australia Group), ARACY, Brotherhood of St. Laurence, cohealth (a Victorian community health

service), Good Shepherd Australia New Zealand, Foodbank Australia, Jesuit Social Services, Life Without Barriers, Mission Australia, SSI and The Smith Family. We would also like to thank our philanthropic partners Hart-line and the

Social Justice Fund – both sub-funds of Australian Communities Foundation –and John Mitchell.

We acknowledge and thank UNSW President and Vice-Chancellor Professor Attila Brungs for his support of this initiative, along with Emeritus Professor Eileen Baldry for her steadfast support; and the ACOSS Board.

Cassandra Goldie, CEO, ACOSS & Carla Treloar, Director, Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Sydney

On average in 2019-20, one in eight people (including one in six children) lived below the poverty line.

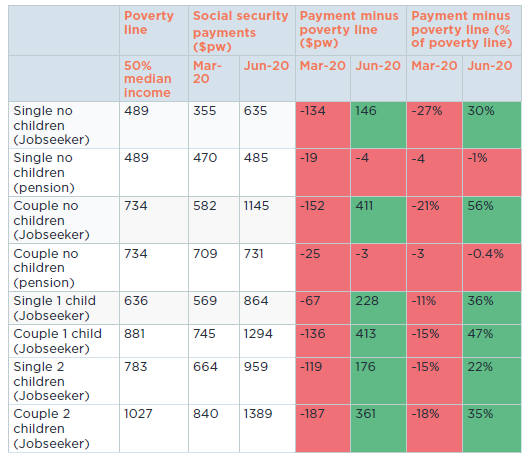

The poverty line based on 50% of median household income ranged from $489 per week for a single person to $1,027 per week for a couple with two children.

More than one in eight people (13.4%) and one in six children (16.6%) lived below the poverty line after taking account of their housing costs. Over three million (3,319,000) people lived in poverty, including 761,000 children.

The following groups faced the highest risk of poverty (20% or more) in 2019-20:

- People in households whose main income-earner was of working age and unemployed (62%) or not in the labour force (47%);

- People in households receiving income support including Newstart Allowance / JobSeeker Payment (60%), Parenting Payment (72%), Youth Allowance (34%), Disability Support Pension (43%) or Carer Payment (39%)1Households in which over 50% of gross income is government cash benefits where those benefits are at least $180 per week. Newstart Allowance was renamed ‘JobSeeker Payment’ in 2020.

- Tenants in public housing (52%) and private rental (20%, and 50% for those aged 65 years and over);

- People in sole parent households (34%, and 39% among children in those households);

- Single people without children (25%, and 26% among those under 65 years);

- People with disability and a ‘core activity restriction’ (20%).

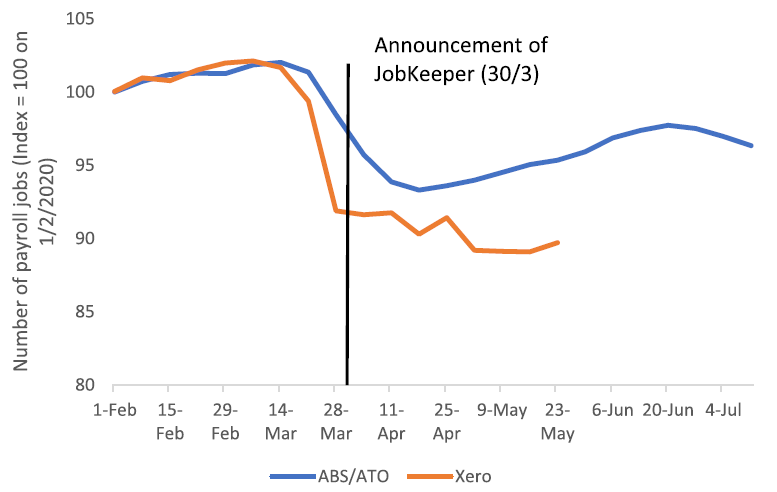

In the March quarter of 2020, COVID lockdowns dramatically increased poverty

Poverty rose from 13.2% of all people (16.2% among children) in the September quarter of 2019 to 14.6% (19% among children) in the March quarter of 2020 as people lost paid hours in COVID lockdowns.

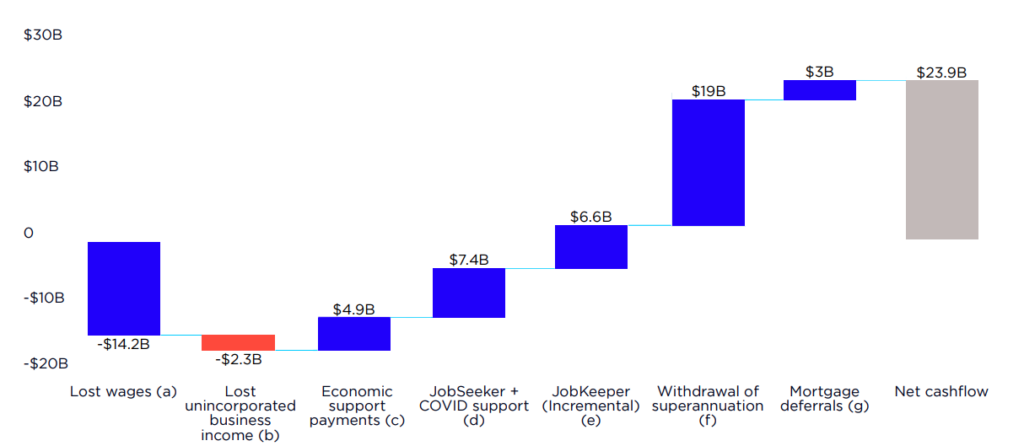

Then in the June quarter of 2020, COVID income supports (especially Coronavirus Supplement) greatly reduced the deepest poverty:

- Poverty fell to 12% (13.7% among children) in the June quarter due to COVID income supports, especially the Coronavirus Supplement and greatly reduced the deepest poverty:

- By one-fifth among people in households whose main income was social security (35% were in poverty on average in 2019-20, but poverty among them fell by 8 percentage points or by 389,000 people between March and June quarters 2020 when COVID income supports began);2It fell from 38% in March to 30% in June. This is 8 percentage points but one fifth (21%) of the rate in March. Note that the March quarter rate, not the average rate for 2019-20 (35%) is the basis for the calculation of poverty reductions in the June quarter.

- By more than half in households mainly relying on JobSeeker Payment (60% in poverty in 2019-20, reducing by 49 percentage points or 262,000 people);

- By around one-third among people in households relying mainly on Parenting Payment (72% in poverty in 2019-20 – reducing by 29 percentage points or 128,000 people);

- By one-third among people in households whose main income earner was unemployed (62% in poverty in 2019-20 – reducing by 25 percentage points or 94,000 people);

- By one-quarter among people renting their homes privately (20% of those renting privately were in poverty in 2019-20 – reducing by 6% or 349,000 people).

Complementing our recent Snapshot of poverty in Australia (2022) and Covid, inequality and poverty in 2020 & 2021 reports, this report sheds more light on the human face of poverty in Australia – who is most affected and why. It examines the extent of poverty at different stages of the life course from childhood to old age, among people in different types of families, among those with disability or caring responsibilities , in households with different income sources and by reference to a range of other characteristics. It offers fresh insights into who lives in poverty and how it might be reduced.

The data used for this report comes from the 2019-20 ABS Survey of Income and Housing, which was conducted just as the COVID recession struck and major improvements were made to income support to shield those affected from hardship. The impacts of these momentous events on poverty in Australia were profound. By comparing poverty levels before and after the introduction of the new COVID income supports in the June quarter of 2020 (including the $275 per week Coronavirus Supplement), we gauge their impact on financial hardship among different groups.3The main factor impacting changes in poverty between the third and fourth quarters of 2019-20 was the introduction of COVID payments and early access to superannuation accounts in the fourth quarter (Attachment 1). Another major influence was changes in income from employment as lockdowns continued or were eased. The impact of COVID income supports on poverty may be understated here, due to time lags in receipt of COVID payments (and reporting them to the ABS) among those surveyed early in the fourth quarter.

We estimate the average levels of poverty throughout 2019-20 among people belonging to different groups in the population, together with changes in their poverty levels after those income supports were introduced. The report shows that high levels of poverty are not inevitable – well targeted investments in income support can make a big difference to people’s living standards and wellbeing.

On average in 2019-20, one in eight people (including one in six children) lived below the poverty line.

The poverty line based on 50% of median household income ranged from $489 per week for a single person to $1,027 per week for a couple with two children.

More than one in eight people (13.4%) and one in six children (16.6%) lived below the poverty line after taking account of their housing costs.

- In total, over three million (3,319,000) people lived in poverty, including 761,000 children.

On average, people in poverty were in households with incomes $304pw below the poverty line.

People in poverty lived in households with incomes averaging $304 per week below the poverty line (the ‘poverty gap’), after deducting housing costs. The average poverty gap was 42% of the poverty line.4This average figure is not adjusted for household size, so it is inflated by the larger poverty gaps among people in larger households. Poverty gaps for single people living in poverty were lower

These average figures conceal large variations over time – poverty rose sharply in the March quarter of 2020 (with COVID lockdowns) then fell sharply in the June quarter (with COVID income supports).

Poverty rose from 13.2% of all people (16.2% among children) in the September quarter of 2019 to 14.6% (19% among children) in the March quarter of 2020, then fell to 12% (13.7% among children) in the June quarter of 2020. These are large shifts in poverty for such a short period, compared with recent Australian and international experience.5See Attachment 2 and Davidson P, Bradbury B, Hill T & Wong M (2020), Poverty in Australia: Overview; Eurostat (2021), ‘Early estimates of income and poverty in 2020’.

- Between the March and June quarters of 2020, the overall number of people in poverty fell by 646,000 including 245,000 children.

The following groups faced the highest risk of poverty (20% or more) in 2019-20:

- People in households relying substantially on Newstart Allowance / JobSeeker Payment (60%), Parenting Payment (72%), Youth Allowance (34%), Disability Support Pension (43%) or Carer Payment (39%);6Households in which over 50% of gross income is government cash benefits where those benefits are at least $180 per week. Newstart Allowance was renamed ‘JobSeeker Payment’ in 2020.

- People in households whose main income-earner was of working age and unemployed (62%) or not in the labour force (47%);

- Tenants in public housing (52%) and people who rented their homes privately (20%, and 50% for those aged 65 years and over);

- People in sole parent households (34%, and 39% among children in those households);

- Single people without children (25%, and 26% among those under 65 years);

- People with disability and a ‘core activity restriction’ (20%).

Over a third of people in households whose main income was social security (35%) were in poverty in 2019-20, but poverty among them fell by one fifth with COVID income supports.

People in households relying mainly on social security payments were five times more likely to be in poverty than those relying mainly on wages (35% compared with 7%).

- Still, 37% of people in poverty lived in households relying mainly on wages (compared with 47% relying mainly on social security) as there were more wage-earning households overall.

The rate of poverty among people in households relying mainly on social security fell by 8 percentage points (389,000 people) when COVID income supports were introduced, compared with a decline of 2% (401,000 people) in households relying mainly on wages.7See footnote 2 for an explanation of these calculations.

Most people in households relying mainly on Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment or Parenting Payment were in poverty in 2019-20, but it fell by half and one third respectively with COVID income supports.

In 2019-20, rates of poverty were especially high where households relied mainly on Parenting Payment (72%), Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment (60%), and Disability Support Pension (43%).

- When the Coronavirus Supplement was added to the lowest income support payments, poverty was reduced by 57 percentage points (262,000 people) for people relying on Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment and 31% (128,000 people, including children) for those relying on Parenting Payment.

- There was little change in poverty for people in households mainly reliant on pensions, which did not attract the Supplement.

Among people in households below the poverty line who relied mainly on income support, poverty was deepest for those relying on Youth Allowance

- On average in 2019-20, people in poverty in households relying mainly on Youth Allowance lived $390pw below the poverty line, $269pw where they relied mainly on Newstart Allowance, and $246pw where they received Parenting Payment.

- Poverty gaps were somewhat lower for Carer Payment ($201), Disability Support Pension ($156) and Age Pension ($118).

Over 60% of people in households whose main income-earner was unemployed were in poverty in 2019-20, but this fell by a third with COVID income supports.

Unemployment is closely associated with poverty. In 2019-20, 62% of people in households whose main earner was unemployed were in poverty.

- However, this was reduced by 25 percentage points (94,000 people) with COVID income supports, demonstrating their effectiveness in easing financial hardship among those unemployed during COVID lockdowns.

While 38% of all people in poverty were in ‘employed’ households (due to the large number of those households) their poverty rate was lower than for those out of paid work:

- 5% of people in households whose main earner was employed full-time were in poverty.

- Poverty declined by 2.5 percentage points or 367,000 people in those households when COVID income supports were introduced.

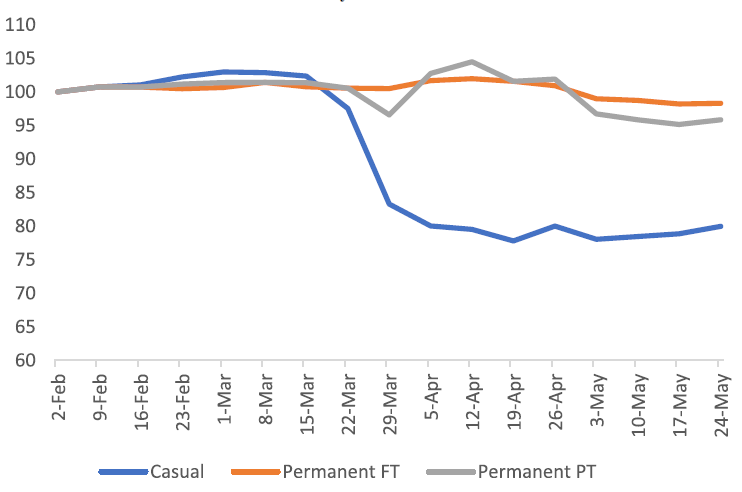

- Poverty was higher (19%) among people in households with main earners employed part-time.

- Poverty among the latter group increased slightly (by 0.1%) with COVID income supports, likely due to ongoing job losses among people working part-time and gaps in supports for them (e.g. the exclusion of short-term casualised staff from JobKeeper Payment).

One fifth of tenants in private rental and half of public housing tenants were in poverty in 2019-20, compared with less than one in ten people who owned or were buying their homes.

Australia’s housing affordability crisis impacted most severely on tenants in private rentals (20% of whom were in poverty) or in public housing (52%). The high poverty rates of tenants in public housing reflected other disadvantages (such as unemployment and low fixed incomes) experienced by this group.

- Poverty among people living in rented homes (private or public) fell by 6 percentage points (383,000 people) when COVID income supports were introduced.

Home ownership offered a degree of protection against poverty, which was much lower among homeowners with and without mortgages (10% and 8% respectively).

Households whose main income-earners were women had almost twice the level of poverty (18% compared with 10%) in 2019-20 as those whose main income-earner was a man.

Since women have much lower incomes on average than men, they and family members relying on them (including women who have never partnered and those affected by separation or death of a partner) faced a greater risk of poverty (18%) than those in households with a main income-earner who was a man (10%).

- In 2019-20, 1,765,000 people were in poverty in households with main income-earners who were women (53% of people in poverty) compared with 1,554,000 (47%) in those with main income-earners who were men.

The JobKeeper Payment went disproportionately to men (including male wage-earners who were stood down or lost their jobs). This, together with the slower restoration of paid working hours for women employed part time, reinforced this gender income bias:

- In the June quarter of 2020, poverty fell by 4 percentage points (604,000 people) in households where the main income-earner was a man, but only by 0.2% (21,000 people) in households where the main income-earner was a woman.

Two fifths of children in sole parent families were living in poverty in 2019-20 compared with one eighth of those in partnered families.

The risk of poverty for children in sole parent families was three times that in partnered families (39% compared with 12%) reflecting the lower incomes of parents who care for a child alone, 83% of whom were women.

- Poverty fell substantially among children in two-parent families (by 6 percentage points or 211,000 children) when COVID income supports were introduced.

- Surprisingly, the decline in child poverty in sole parent families was only small (0.3% or 3,000 children), though as noted it fell by 29% among those receiving Parenting Payment.8One reason for this was the design of the Coronavirus Supplement which was less generous for single income families compared with couples. Another reason is that employment among sole parents (who were often employed in casual and part-time service industry jobs) took longer to recover from COVID lockdowns.

Poverty was highest among younger and older people in 2019-20, but COVID income supports did much to reduce it among children and young people.

The average rate of poverty in 2019-20 was 17% among children, 14% among young people 15-24 years of age, 12% among people aged 25-64 years, and 14% among older people.

When COVID income supports were introduced, poverty declined by 5 percentage points (245,000) among children, by 4% (115,000) among young people and by 2% (300,000) among people aged 25-64 years, but it increased by 0.5% (21,000) among older people.

- The relative generosity of COVID payments towards people of working age reflects their main purpose, which was to support people unable to secure or remain in paid employment due to COVID lockdowns. Many of those affected were young workers or parents.

- The small increase in poverty among older people likely reflects declining investment incomes as financial markets came under strain during COVID lockdowns. On the other hand, poverty among older people who rent (who are more likely to face financial hardship) fell by 8% (33,000 people).

COVID income supports demonstrated that governments can substantially reduce poverty.

COVID income supports (especially the Coronavirus Supplement) were well targeted to reduce poverty among key high-risk groups including people in households whose main income-earner was unemployed, people of working age and their families, and people renting their homes.

They were less well targeted to reduce poverty among other high-risk groups, including single people with and without children and households whose main income-earners were women.

There are lessons here for future policies including the importance of lifting the lowest income support payments for people of working age (such as Youth Allowance and JobSeeker Payment), the need to get the relativities right between payments for single and partnered people, and for income support to better meet the needs of people in casual and part-time jobs (most of whom are women).

The solutions to poverty remain clear.

More broadly speaking, the evidence supports the following policies to reduce poverty:

- Lift the lowest income support payments (including Youth Allowance and JobSeeker Payment) to at least pension levels to shield people of working age and their families from poverty when they cannot obtain enough paid work.

- Introduce and improve supplements to cover essential costs above and beyond basic income support, including the extra costs of sole parenthood and disability.

- Commit to full employment based on targets which guarantee there are enough jobs and paid working hours overall for people who need them.9Baker D & Bernstein J (2014), Getting Back to Full Employment. CCF Brief # 52, Brookings Institution, Washington

- Invest in effective employment services to end the entrenched economic exclusion of people such as those unemployed long-term, First Nations communities, people with disability and older people; and to improve access to decent jobs and careers for people entering or returning to paid work including young people, parents and carers.10Davidson P (2020), Faces of unemployment. ACOSS, Sydney.

- Build more social housing and increase Rent Assistance to improve the supply of secure and affordable homes and help those on the lowest incomes with their largest living expense.

This is Part 2 of the Poverty in Australia report, following publication of our Poverty in Australia 2022: A snapshot in October 2022. The latest report of the Poverty and Inequality Partnership led by ACOSS and UNSW (Sydney), this report updates estimates of poverty from our six previous poverty reports.11The companion publication, ‘Inequality in Australia’ profiles income and wealth inequality.

The purpose of this report is to break the overall figures down to show how rates of poverty vary among different demographic groups and people with different sources of income. An innovation of this report is that we compare poverty levels among different groups in the third and fourth quarters of 2019-20 to infer the impact of major improvements in income support introduced during the COVID recession.

For the purpose of this report, people are in poverty when their household’s disposable income falls below a level considered adequate to achieve an acceptable standard of living. Rather than measure living standards directly (for example, by asking people whether they have to go without necessities), we set a benchmark for the adequacy of household incomes of one-half (50%) of the median or ‘middle’ household disposable income. This is the ‘poverty line’. We also report the number of people who fall below a higher poverty line set at 60% of median household disposable income on the ACOSS/UNSW Sydney Poverty and Inequality Partnership website.12The 50% of median income poverty line is used by the OECD, while the higher 60% of median income poverty line is used by the European Union. We differ from the OECD approach by also subtracting housing costs from after-tax income. (Some of the published results from the OECD also use a different adjustment for household size). Australia does not currently have an official national poverty line, despite our obligation under the Sustainable Development Goals to ‘by 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions. See: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/poverty/.

In this way, we measure poverty by comparing the spending capacity of people with low incomes with that of ‘middle Australia’.

It does not follow that we are simply measuring overall inequality, or that poverty cannot be eliminated while income inequality exists. It can be eliminated by lifting the lowest incomes (including social security payments, paid working hours and minimum wages) to at least half the median level. One of the most important lessons of the COVID recession is that poverty is impacted by changes in economic conditions and the policy responses to those changes – in this case the introduction of COVID income supports.

People’s spending power is affected by more than their incomes. This report also takes account of two factors that have a large impact on the ability of a household to live decently at a given level of income.

First, we adjust (or ‘equivalise’) disposable incomes to take account of family size. Clearly, a couple with two children needs more money to achieve the same living standard than a single person living alone. Poverty lines are adjusted in this way, as illustrated in Table 1. So the 50% of median income poverty line for a single person was $489pw in 2019, and that for a couple with two children was $1,027pw.

Second, we take account of variations in the largest fixed cost of most low-income households: housing. At a given level of income, outright homeowners can achieve a much higher standard of living than most tenants or people with mortgages because their housing costs are lower. This is especially important when measuring poverty among older people.

This research takes housing costs into account by subtracting them from disposable income before calculating the median, generating a set of

lower ‘after-housing’ poverty lines (not shown here as they are not directly comparable with household disposable incomes). The after-housing costs

poverty line is the amount of money needed to buy all other essentials after housing is paid for. The poverty status of each household is established by deducting its housing costs from its disposable income and comparing the remaining amount with the after-housing costs poverty line.

Table 1: Poverty Lines by family type, 2019-20

Note: The main poverty line used in this report is 50% of median income. Amounts correspond to household after-tax incomes, including social security payments and investment incomes as well as wages.

We report the results of this research in three ways.

First, we report the percentage of individuals belonging to different groups (such as children) in households living below the 50% of median income poverty line.13The data used are from the latest ABS Survey of Income and Housing (2019-20). We exclude from the survey sample households reporting zero or negative incomes and self-employed households, since their reported incomes may not be good indicators of their living standards. Estimates of the total number of people who are below the poverty line (as opposed to the poverty rate) compensate for these exclusions by inflating the estimates by the ratio of the total population to the non-excluded population. For the overall estimate of poverty numbers, this is equivalent to assuming that the excluded households (e.g. self-employed households) have the same poverty rate as those not excluded. This gives us estimates of the rate of poverty for each group.

Second, we report the number of individuals living below the 50% of median income poverty line that belong to different groups. This allows us to profile people in poverty (for example, the percentage of all individuals in poverty who are children).

Third, we calculate ‘poverty gaps’ for people living below the poverty line. This tells us about the depth or severity of poverty: how far below the poverty line are those living in poverty? The poverty gap is expressed in 2021 dollars per week.

In this report we take advantage of the fact that the ABS income survey from which these numbers are derived was conducted during the year in which COVID lockdowns were imposed and temporary COVID income supports were introduced. This gives us an unprecedented opportunity to track the impact of the deepest recession in over 80 years, and the largest increase in income support payments since they were first introduced, on poverty among different groups:

- Poverty increased sharply in the third quarter of 2019-20 (January to March 2020) with the onset of the COVID recession, as many people lost jobs or paid working hours;

- It decreased sharply in the fourth quarter of 2019-20 (April to June 2020) when COVID income supports (especially Coronavirus Supplement and JobSeeker Payment) were introduced.14As discussed in Attachment 1, these were the main influences on changes in poverty at those times. There were also confounding factors that worked in different directions. For example, large-scale job losses continued between April and May 2020, disproportionately impacting some groups such as sole parents. Further, lags in the take-up of COVID income supports would also influence poverty rates in the fourth quarter of 2019-20.

To clearly identify these impacts on low-income households, we use the same poverty line (adjusted for inflation) across the four quarters of 2019-20. Further information on the methods used to produce the estimates in this report is contained in the Methodology Page of the Poverty and Inequality Partnership website.

After taking account of housing costs, on average in 2019-20 one in eight people (13.4%) and one in six children (16.6%) lived below the poverty line. Over three million (3,319,000) people lived in poverty, including 761,000 children.

The table below compares average rates of poverty in 2019-20 among different groups in the community (the percentage of people belonging to each group in poverty) and also the number of people in each group in poverty. Note that poverty is a household measure, so the people in poverty shown here are members of households living below the poverty line.

A unique feature of this report is that we compare levels of poverty among different groups before and after the introduction of temporary COVID income supports (especially the Coronavirus Supplement and JobKeeper Payment) to assess their impact on poverty. The infographic therefore compares rates and levels of poverty before and after the introduction of those income supports.15Note that the changes in poverty in the last two columns are the difference in poverty levels between the March and June quarters of 2020. As such, they be subtracted from the average levels of poverty throughout the year as a whole in the first two columns. Note also that factors other than COVID income supports – especially changes in paid working hours as lockdowns were imposed and lifted – affected changes in poverty at that time, though the introduction of COVID income supports were the main influence. Analysis in the Attachment to this report indicates that the average poverty rates for 2019-20 are close to those for the period from 2009 to 2017, despite the volatility of poverty levels in 2019-20 (a large increase in the third quarter due to a recession followed by a large reduction when COVID income supports commenced in the fourth quarter).

The table does not include results when the higher 60% of median income poverty line (used by the European Union) is used. Those figures are published on the ACOSS/UNSW Sydney Poverty and Inequality Partnership website.

The following groups faced the highest risk of poverty (20% or more):

- People in ‘income support households’ receiving Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment (60%), Parenting Payment (72%), Youth Allowance (34%), Disability Support Pension (43%) or Carer Payment (39%);16Households in which over 50% of gross income is government cash benefits where those benefits are at least $180 per week. Newstart Allowance was renamed ‘JobSeeker Payment’ in 2020.

- More broadly, people in households whose main income was social security (35%);

- People in households whose main income-earner was of working age and unemployed (62%) or not in the labour force (47%);

- Tenants in public housing (52%) and tenants renting privately (20%, and 50% for those aged 65 years and over);

- People in sole parent households (34%, and 39% among children in those households);

- Single people without children (25%, and 26% among those under 65 years); and

- People with disability and a ‘core activity restriction’ (20%).

Regrettably, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) survey on which these data are based does not identify Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. A separate study by Markham & Biddle (2017), estimated that 31% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were living in poverty in 2016.17This estimate is derived from 2016 Census data, using a before-housing poverty measure and the same equivalence scale as the present study. This is likely to result in a lower poverty rate than the method used in this study because ‘before-housing’ poverty rates are generally lower. Further, the relatively high level of non-declaration of income among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander census respondents reduces estimated poverty rates (Markham F & Biddle N 2017, Income, poverty and inequality – Census Paper 2 Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, Canberra).

Broadly speaking, when COVID income supports were introduced poverty fell the most among those at greatest risk of it. The following groups had the largest reductions in poverty (of at least 5 percentage points compared with 2.6% overall) when COVID income support payments commenced:

- People in ‘income support households’ receiving Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment (-49%), or Parenting Payment (-29%).

- More broadly, people in households whose main income was social security (-8%).

- People in households whose main income-earner was of working age and unemployed (-25%) or not in the labour force (-13%).

- Public and private tenants (-6%).

- Children (-5%) especially those in ‘couple with children’ households (-6%); and

- Migrants from countries other than ‘main English-speaking countries’ (-5%).

Table 2: Rates of poverty and number of people in poverty in 2019-20, and changes in poverty after COVID income supports were introduced

Note: Values highlighted in red are poverty rates of 20% or more (rounded). Values in green are reductions in poverty of at least 5 percentage points.

Income support households = Households in which over 50% of gross income is government cash benefits and those benefits are at least $180pw.

(1) Refers to all persons in the survey with this characteristic (2) Refers to persons in households with this characteristic (3) Refers to persons in households where the reference person (see footnote) has this characteristic (4) Refers to adults with this characteristic (5) Percentage-point reduction.18The household reference person (elsewhere referred to here as the ‘main income earner’) is selected by the ABS as follows, from among people aged 15+ in the household: The first unique person chosen is described as the reference person. Highest tenure (ranked: owner, owner with mortgage, renter, other), a member of a couple with dependent children, a member of a couple without children, a lone parent, the person with the highest income, the oldest person. Where the reference person is a member of a couple, in 95% of cases the reference person has a higher income than their partner, in 4% of cases they have equal income, and in 1% the reference person has a lower income. * Small sample size.

This chapter examines rates of poverty and numbers of people in poverty among different groups in the population in 2019-20 in more depth, along with changes in poverty when COVID income supports were introduced. Factors contributing to poverty levels for each group are briefly discussed.

For readers who wish to compare poverty rates based on the higher 60% of income poverty line, these data can be found at http://povertyandinequality.acoss.org.au.

4.1 Age

Average levels of poverty in 2019-20

The average rate of poverty declines until people reach retirement age, then increases (Figure 1). However, the largest group living in poverty are people of working age (1,535,000 out of 3,320,000 people or 46% of those in poverty) as that is the largest age cohort in the overall population (Figure 2).

The rate of poverty among children (discussed in detail below) is higher than average at 16.6% (761,000 children) compared with the overall average rate of 13.4%.

Poverty among young people (15-24 years) is also above-average at 14%, or 419,000 young people. Young people face relatively high rates of unemployment and under-employment (inadequate paid hours) and many are out of the labour force while studying fulltime.19Foundation for Young Australians (2019), The new work reality. Melbourne.

Among people aged 25 to 64 years, the poverty rate is below-average at 11.9% (1,535,000 people), reflecting the higher earnings of this age cohort.

People aged 65 years and over who own or are buying their home are less likely to experience poverty than the rest of the population (9.6%). One reason for this is that (as discussed later) the Age Pension is close to the poverty line so that modest levels of investment and other income lift them above the line. However, poverty is much higher (49.7%) among the one in eight older people who rent their homes, due to their much higher housing costs.20ABS, Housing Occupancy and Costs, Australia, 2019–20.

Change in poverty by age group with COVID income supports

Poverty declined significantly for all age groups except older people when COVID incomes supports were introduced in the last quarter of 2019-20.

Child poverty declined substantially by 5.3 percentage points for reasons discussed below.

Poverty among young people fell substantially by 3.8% or 115,000 young people, likely due to the improved safety net offered by COVID payments (Coronavirus Supplement and JobKeeper Payment) for those out of paid work, especially those receiving Youth Allowance (see Part 4.5 Social security payments). This outcome was remarkable as young people (who are more likely to be employed on a casual basis) were disproportionately impacted by the recession. The number of jobs held by people under 25 years fell by 17% from March to May 2020, compared to an overall decline of 7%.21Kabatek J (2020), Jobless and distressed: the disproportionate effects of COVID-19 on young Australians. Melbourne Institute Research Insight 26/20; ABS (2020), Labour Force, Australia.

Poverty among people of ‘working age’ fell by 2.3% or 300,000 people for the same reason.

Poverty among older people rose slightly by 0.5% or 21,000 people. It rose more significantly among those who owned or were purchasing their homes (by 2.9% or 114,000 people) but fell sharply among the smaller population of older people renting their homes (by 7.6% or 33,000 people). The likely reason for the rise in poverty among older homeowners is a decline in investment incomes (discussed in Part 4.4 Main income source). The likely reason for lower poverty among those renting their homes was the lump sum COVID payments paid to people on Age Pension and other pensions at this time, together with temporary rent freezes (see 4.5 Social security and 4.9 Housing tenure).

Figure 1: Rates of poverty by age in 2019-20, and change in poverty (% of people)

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show average rates of poverty by age in 2019-20. Red bars show the increase or decrease in poverty from March to June quarters of 2020 (in percentage points). Note that these changes in poverty cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures.

Figure 2: Number of people in poverty by age in 2019-20, and change in poverty

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show average number of people in poverty by age in 2019-20. Blue bars show the increase or decrease in poverty from March to June quarters of 2020. Note that these changes in poverty cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures.

(1) Child poverty

As indicated above, 761,000 children (16% of all children) were living in poverty in 2019-20 (Figure 1). Contributing factors include the impact of caring responsibilities on parents’ employment participation, the direct costs of children (as measured using the equivalence scale), and the inadequacy of government financial assistance to families, including income support and Family Tax Benefits.22The poverty lines used in this research take account of the needs of different-sized households using equivalence scales (see methodology section).

The risk of poverty is highest for children in sole parent families (Figures 3 and 4):

- 39% of children in those families (316,000 children) were in poverty in 2019-20, more than three times the poverty rate for children in couple families (13%).

- However, since 82% of families with children lived with two parents, most children in poverty were in couple families (431,000 children) rather than sole parent families (316,000 children).23ABS (2019), Labour Force Status and Other Characteristics of Families, June 2019

Factors contributing to the higher rates of child poverty in sole parent families include reliance on a single parental income and lower employment levels among sole parents (due to a combination of their sole caring responsibilities, childcare availability, and limited flexible employment options). In June 2019, 62% of sole parents with a dependent child under 16 years were employed compared with 93% of couple families where at least one partner was employed.24ABS (2019), ibid. This means a higher proportion of sole parents rely on social security payments, which generally sit below the poverty line. Poverty among sole parent families without paid work deepens when the youngest child reaches eight years and the parent is transferred from Parenting Payment to the lower JobSeeker Allowance.25See Part 4.5 Social security payments. Baxter J et al (2012), ‘Parental joblessness, financial disadvantage and the wellbeing of parents and children’ Occasional Paper No. 48, Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, Canberra.

Change in child poverty with COVID income supports

Poverty among children fell substantially, by 5.3 percentage points or 245,000 children, when COVID income supports were introduced (Figures 3 and 4). The main reason was likely to be the Coronavirus Supplement which boosted the incomes of families on the lowest income support payments including JobSeeker Payment and Parenting Payment.

Surprisingly, the decline in child poverty in sole parent families was only small (0.3% or 3,000 children) compared with the large reduction in couple families with children (5.9% or 211,000 children). Likely reasons for this are discussed below in Part 4.3 Family type.

Figure 3: Rate of poverty in 2019-20, and change in poverty, among children up to 15 years

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show child poverty rates (under 15 years) in 2019-20. Blue bars show the increase or decrease in poverty from March to June quarters of 2020 (in percentage points).

‘Other’ households are mixed (e.g. multi-family) households.

Note that these changes in poverty cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures.

Figure 4: Number of children in poverty in 2019-20, and change in child poverty

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show average number of children (under 15 years) in poverty in 2019-20. Blue bars show the increase or decrease in poverty from March to June quarters of 2020.

‘Other’ households are mixed (e.g. multi-family) households.

Note that these changes in poverty cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures.

4.2 Gender

Figure 5 shows that women were more likely to live in households below the poverty line than men (13.9% as against 12.9% for men) while Figure 6 shows that the majority of people in poverty (1,754,000 out of 3,320,000 people, or 53%) were women or girls.

This report adopts the conventional approach to poverty research and focusses on household incomes. While beyond the scope of this study, it is worth noting that if we focused instead on differences in personal incomes between men and women, the gaps between them are likely to be much larger.26See the detailed discussion of gender and poverty in our previous report: Davidson P, Bradbury B, Hill P & Wong M (2020), Poverty in Australia 2020: Part 2 – Who is affected.

Another way to compare the risk of poverty among men and women is to compare poverty in households where the main income-earner is a man or a woman. If women have lower earning-capacity than men, we expect (all things equal) the risk of poverty to be greater in households where women are the main income earners. For this purpose, we use the ABS measure of ‘household reference person’ as a proxy for the highest earner in a household.27While this is not always the same person as the highest earner, it is in the vast majority of cases. The household reference person is selected by the ABS as follows, from among people aged 15+ in the household: The first unique person chosen is described as the reference person. Highest tenure (ranked: owner, owner with mortgage, renter, other), a member of a couple with dependent children, a member of a couple without children, a lone parent, the person with the highest income, the oldest person. We use reference person here as a proxy for ‘highest income-earner’. Where the reference person is a member of a couple, in 95% of cases the reference person has a higher income than their partner, in 4% of cases they have equal income, and in 1% the reference person has a lower income.

Figure 5 shows that the difference between poverty rates for all individuals in households with men and women as reference person is indeed much greater than that between men and boys and women and girls generally (shown above). The poverty rate in households where the reference person was a woman was 18.1% compared with 10.4% where the reference person was a man.

Figure 6 shows that there were 1,765,000 people in poverty (men, women and children) in households where the main earner was a woman compared with 1,554,000 people where the main earner was a man.

Change in poverty by gender with COVID income supports

Figure 5 shows that when COVID income supports were introduced, poverty fell much more in households where the main earner was a man (by 4% or 604,000 people) while the decline in poverty where the main earner was a woman were minimal (0.2% or 21,000 people).

A likely reason for this is the very different labour market experience of women and men during COVID lockdowns. From February to May 2020, employment among women fell by 7.1% compared with 5.6% among men and those job losses persisted through the last quarter of 2019-20.28Borland J & & Charlton A (2021), ‘The Australian labour market and the early impact of COVID19’. Australian Economic Review, Vol 53 No 3, pp 297-324. This was due to a combination of the higher proportion of women in casual jobs and personal service occupations vulnerable to COVID lockdowns, and the withdrawal of many women from the paid workforce to care for children as childcare services and schools closed.29In March 2020, 26% of female employees were engaged on a casual basis compared with 23% of male employees (Wood D et al 2021, Women’s work: The impact of the COVID crisis on Australia’s women. Grattan Institute). Over a quarter of women employees (27%) were in the (relatively low paid) community and personal services and sales occupations, where the greatest reductions in employment from February to May 2020 occurred, by 29% and 17% respectively. (Borland J & Charlton A 2021, op cit; ABS 2020, Labour Force Australia, detailed). Among women who lost employment between February and May 2020, 50% reported that their ‘main activity’ in May 2020 was caring for family members, compared with 17% of men who lost their jobs (Biddle N et al 2020, Changes in paid and unpaid activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods). Where the women affected by job losses were the main income earners in a household – including the sole parent families discussed in Part 4.3 below and single women living alone), there was a greater likelihood that the household would fall into poverty.

These gender inequities in the labour market were reinforced by the JobKeeper Payment, of which 55% of recipients were men during the first six months of the program. The exclusion of people on short-term (less than one year) casual contracts from this payment disproportionately impacted women, 26% of whom were employed on a casual basis.

Figure 5: Rate of poverty in 2019-20, and change in poverty, by gender

[infogram id=”_/maUUW1iQSW3yszw20foy” prefix=”akx” format=”interactive” title=”2019-20: Rate of poverty by gender (% of men and women)”]

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show poverty rates by gender in 2019-20. Blue bars show the increase or decrease in poverty from March to June quarters of 2020 (in percentage points).

ABS does not collect data on people who are gender-diverse. The person identified by ABS as ‘household reference person’, is, in the vast majority of cases, the adult household member with the highest income.

Note that these changes in poverty cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures

Figure 6: Number of people in poverty by gender in 2019-20, and change in poverty

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show average number of people poverty by gender in 2019-20.

Blue bars show the increase or decrease in poverty from March to June quarters of 2020.

ABS does not collect data on people who are gender-diverse.The person identified by the ABS as ‘household reference person’, is, in the vast majority of cases is the adult household member, with the highest income.

Note that these changes in poverty cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures.

4.3 Family type

Figure 7 shows that, consistent with the higher rate of child poverty in sole parent families discussed above, this family type had the highest rate of poverty, with 34% of all people (adults and children) in sole parent families living in poverty. However, the largest number of people in poverty are found in couple-with-children families (1,076,000 people compared with 665,000 people in sole parent families) due to the greater number of couple-with-children families overall (Figure 8).

Single people living alone also had relatively high poverty rates, reflecting their limited economies of scale in living costs (taken into account when we adjust incomes for household size), and their reliance on a single income. Single adults under 65 years have a slightly higher rate of poverty (25.6%) than those 65 years and older (24.7%).

Poverty was relatively low among couples without children (8% in couple families of working age and 12.5% among older couples) due to their higher incomes and greater economies of scale compared with single people.

Change in poverty by family type, with COVID income supports

Poverty fell substantially by 5.1 percentage points (509,000 people) in couple-with-children families and fell slightly in single person households of working age and among older couples -by 0.3% or 5,000 people and 0.5% or 12,000 people respectively (Figures 7 and 8). Most of the overall reduction in poverty (647,000 people) occurred in couple-with-children families.

In contrast to couples with children, poverty among people (including children) in sole parent families rose slightly by 1.1 percentage points (21,000 people) in the June quarter of 2020.

Employment among sole parents (who were relatively likely to be employed in casual part-time jobs) took longer to recover as COVID lockdowns were eased and many withdrew from the paid workforce to care for their children as childcare was no longer available.30See Attachment 1 and Wood D et al (2021), op cit. From March to April 2020, the number of sole parents employed fell by 10% compared with a 3% reduction among couple parents. By June 2020, employment among both sole parents and couples with children had increased by 2 percentage points, restoring some of the jobs lost. Similarly, from March to April 2020, workforce participation among single mothers fell by 10% and their paid working hours fell by 20%, compared with falls of 3% an 13% respectively among partnered mothers. As childcare services and schools closed under lockdowns, sole parents had little option to care for younger children fulltime. By June 2020, around half these reductions in workforce participation and paid hours for single and partnered mothers were restored as lockdowns were eased and the economy recovered but sole parents started from a lower base. Sole parents comprised 5% of people employed on a casual basis for less than 12 months (Cassels R & Duncan A 2020, Short-term and long-term casual workers: how different are they? Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre Research Brief COVID-19 #4. Perth).

Also, COVID income supports were less accessible and generous for sole parents:

- As discussed previously, JobKeeper Payment was not available to people employed on a casual basis for less than a year (which included many sole parents).

- Further, the Coronavirus Supplement for couples was twice the rate paid to single people. The economies of scale available to couples (taken into account in the equivalence scale used in this poverty research) suggest that couples need approximately 50% more income than a single person, not twice as much.31Treasury (2021), op cit.

On the other hand, poverty fell substantially among sole parent families in households mainly reliant on income support, who were less likely to be in paid employment when lockdowns commenced (see Part 4.5 Social security payments).

Poverty also rose slightly among couples of working age without children (by 0.5% or 14,000 people) and older single people (by 1.9% or 24,000 people). Reasons for a slight increase in poverty among older people were discussed previously in Part 4.1, Age.

Figure 7: Rate of poverty in 2019-20, and change in poverty, by family type

[infogram id=”_/cnf3xtKIsa17rmh6GoPH” prefix=”pQa” format=”interactive” title=”2019-20_Poverty rates by family type”]

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show average rates of poverty by family type in 2019-20.

Blue bars show the increase or decrease in poverty from March to June quarters of 2020 (in percentage points).

‘Other’ households are mixed (e.g. multi-family) households.

Note that these changes in poverty cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures.

Figure 8: Number of people in poverty by family type in 2019-20, and change in poverty

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show average number of people poverty by family type in 2019-20.

Blue bars show the increase or decrease in poverty from March to June quarters of 2020.

‘Other’ households are mixed (e.g. multi-family) households. Note that these changes in poverty cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures.

4.4 Main income source of household

People in households relying mainly on social security payments were five times more likely to experience poverty (35.1%) than those relying mainly on wages and salaries (7% – Figure 9).

The high risk of poverty for households relying on social security reflects the low level of income support and family payments, which (as discussed later) generally sat below the poverty line. Minimum fulltime wages were generally above the poverty line, unless a single wage supported a couple or family with children.32Fair Work Commission (2021), Statistical report, – Annual wage review 2020–21, Melbourne. The living standards of households reliant on social security payments and minimum wages are also examined in depth in ‘budget standards’ research (Saunders P & Bedford M 2017, New Minimum Income for Healthy Living: Budget Standards for Low-Paid and Unemployed Australians, University of New South Wales, Sydney). However, the rate of poverty among households mainly relying on wages rose over the last decade from 5% in 2009 to 7% in 2019, reflecting weak wage growth compared to other components of income.33Treasury (2017): Analysis of wage growth, Canberra.

Half of people in poverty were in households relying mainly on social security (1,626,000 or 49% of all people in poverty – Figure 10). Over one-third of people in households in poverty relied mainly on wages (1,257,000 people or 38% of all people in poverty), reflecting the large number of wage-earning households overall.34The share of households in poverty whose main source of income is wages and salaries rose significantly over the last decade, up from 31% in 2009-10.

Change in poverty by main income source, with COVID income supports

Poverty fell substantially (by 8.4 percentage points or 389,000 people) among people in households mainly reliant on social security (Figures 9 and 10). This was likely due to the $275 per week Coronavirus Supplement which almost doubled many of the lowest payments (see Attachment 1).

It also fell substantially – by 2.2 percentage points or 401,000 people – among people in households mainly reliant on wages, likely due to the introduction of JobKeeper Payment.35Since the poverty rate for this group in the third quarter of 2019-20 was 8.3%, a 2.2 percentage point decline is a reduction in poverty of more than one quarter. Many people employed part-time experienced an increase in their earnings at this time since JobKeeper Payment was then paid at the same flat rate of regardless of hours worked. Consistent with this, financial stress among households whose main income was from low-paid employment fell substantially in 2020 compared with 2019.36The percentage of those households reporting any form of financial stress fell from 32% to 24% (Fair Work Commission (2022), Statistical Summary, Annual Wage Review. Melbourne).

On the other hand, poverty rose slightly (by 1% or 25,000 people) among people mainly reliant on ‘other’ income, which in this report mainly refers to investment income.37For the purpose of measuring poverty, we have excluded self-employed people from the sample (see Methodology Page of our Poverty and inequality research website). This is consistent with the findings of other research.38Biddle N et al (2020), Tracking outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic (November 2020). ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, Canberra. The likely reason for this was the fall in share-markets at the outset of the COVID recession together with a sharp decline in interest rates.39Davidson P, Bradbury B & Wong M (2022), op cit.

Figure 9: Rate of poverty in 2019-20 and change in poverty, by main household income source

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show average rates of poverty by main household income source in 2019-20.

Blue bars show the increase or decrease in poverty from March to June quarters of 2020 (in percentage points).

‘Other income’ includes superannuation and investment income. Note that these changes in poverty cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures.

Figure 10: Number of people in poverty by main household income source in 2019-20, and change in poverty

[infogram id=”_/BDFbdUK0zSR9B0Pg5osf” prefix=”z0s” format=”interactive” title=”2019-20_ Number of people in poverty by main income source”]

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show average number of people in poverty by main household income source in 2019-20.

Blue bars show the increase or decrease in poverty from March to June quarters of 2020.

‘Other income’ includes superannuation and investment income.

Note that these changes in poverty cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures.

(1) Poverty gaps by main income source

The poverty gap is a measure of the depth of poverty. It is the average gap between the incomes of households in poverty and the poverty line, expressed here in 2021 dollars per week.

Figure 11 shows the average poverty gap for households by main income source, and how that changed when COVID income supports were introduced in the fourth quarter of 2019-20.

Households in poverty that were mainly reliant on social security were on average $234 per week below the poverty line. This average figure was inflated by the higher poverty gaps for larger households.40Poverty gaps are shown here as dollars per week and are not adjusted for household size.

Average poverty gaps were higher for households relying mainly on wages ($324) or investment and other incomes ($499). A likely reason for this was that many of those households did not receive social security payments and relied instead on their savings or other sources of support.41See Saunders P & Naidoo Y (2020), ‘The overlap between income poverty and material deprivation: sensitivity evidence for Australia.’ Journal of Poverty and Social Justice Vol 8 No2 pp187–206 for discussion of the importance of wealth holdings in shielding people with incomes below the poverty line from deprivation of essentials. As discussed above, rates of poverty among households relying mainly on wages or other incomes were much lower than for households relying mainly on social security.

Figure 11 shows that average poverty gaps for households mainly relying on social security fell substantially, by an average of $81 per week, when COVID income supports were introduced. By lifting the lowest social security payments they likely reduced both the level and depth of poverty.42Poverty rates and gaps do not necessarily rise and fall in tandem. For example, when pensions were increased in 2009, the overall level of poverty declined substantially but the average poverty gap increased (See Davidson P, Saunders P, Bradbury B & Wong M (2018), Poverty in Australia 2018. ACOSS/UNSW Poverty and Inequality Partnership Report No. 2, Sydney: ACOSS). The reason for this was a compositional effect: many people on pension payments had incomes just below the poverty line before the reform, which lifted them just above it. However, that reform did not lift the lowest income support payments (including Newstart Allowance) so the profile of population of people reliant on income support living below the poverty line became more financially disadvantaged and the average poverty gap increased.

Average poverty gaps for households mainly relying on wages or ‘other’ incomes rose (by $25 and $50 respectively), likely due to a change in the profile of households below the poverty line relying mainly on wages or investment income at this time. For example, after 401,000 (mainly) wage-earning households were lifted above the poverty line (Figure 10), the profile of those remaining below the line was probably more (financially) disadvantaged.

Figure 11: Average poverty gap by main source of income ($pw)

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show average gap between the income of people in poverty and the poverty line in 2019-20 dollars per week, by main household income source in 2019-20.

Blue bars show the increase or decrease in the poverty gap from March to June quarters of 2020.

Other income’ includes superannuation and investment income.

Note that these changes in poverty gaps cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures.

4.5 People mainly reliant on social security payments

Figures 12 and 13 show poverty rates and numbers of people in poverty among people in households mainly reliant on income support payments (‘income support households’).43We define these as households in which over 50% of gross income is government cash benefits and those benefits are at least $180 per week. In previous Poverty in Australia Reports we focussed on households whose reference person (main income-earner) received any income support payment (including small amounts of part-payments where the household had significant private income). We focus on ‘income support households’ here to capture the impacts of COVID income supports on people on income support who faced the greatest risk of poverty. Across all income support payments, these poverty rates averaged 34% (1,453,000 people).

The highest poverty rates among people in ‘income support households’ were for those receiving Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment (60% or 323,000 people) or Parenting Payment (72% or 320,000), followed by Disability Support Pension (43% or 311,000) Carer Payment (39% or 82,000), Youth Allowance (34% or 21,000) and Age Pension (17% or 396,000).44In March 2020 Newstart Allowance was renamed JobSeeker Payment. This payment was received by people in all family types, while Parenting Payment (PP) was received by the main carer of a child aged 7 years or less, whether in a sole parent or couple family. Care should be taken in interpreting the result for Youth Allowance as the sample of people in income support households relying mainly on that payment in the ABS survey is small.

The higher poverty rates for people relying on working age payments (compared with Age Pension) are due to a combination of lower private incomes (many people on Age Pensions, including in ‘income support households’, also received investment income such as superannuation), higher housing costs (as discussed previously most older people owned or were purchasing their homes) and family composition (for example the costs of children in households reliant on Parenting Payment).

Altogether, almost one and a half million (1,453,000) or 44% of all people in poverty were in ‘income support households’ (Figure 12). Despite the relatively low poverty rate among households receiving Age Pension, around one quarter (27%) of ‘income support households’ in poverty relied on that payment. This is due to the relatively large number of people on Age Pensions overall. Further, among ‘income support households’ in poverty, 22% received Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment, 22% received Parenting Payment and 21% received Disability Support Pension.

Change in poverty among ‘income support households’, with COVID income supports

Poverty declined by 8 percentage points (341,000 people) among people in ‘income support households’ (Figures 12 and 13). Poverty in ‘income support households’ relying on Newstart Allowance / JobSeeker Payment fell by 49 percentage points or 262,000 people, and for those on Parenting Payment it fell by 29% or 128,000 people.45These are percentage-point reductions in poverty between the third and fourth quarters of 2019-20 (not compared with the overall average poverty rates for that year shown in Figure 12). Poverty rates in the third quarter of 2019-20 were 87% for those relying on Newstart Allowance and 93% for those relying on Parenting Payment, respectively. So for example among income support households relying on Newstart Allowance, there was a 49 percentage point reduction off the 87% poverty rate in the third quarter. Another way to express this is that the rate of poverty fell by more than half, or 56% (49 divided by 87). We have not included estimates for the reduction in poverty where an income support household received Youth Allowance, due to small sample sizes. However, the low rate of Youth Allowance in March 2020 (see Table 3 below) suggests that the reduction in poverty was probably greater than for other payment types.

These historically large reductions in poverty were largely due to the Coronavirus Supplement which lifted the maximum rate of those payments above the poverty line (as discussed below).46Our previous Poverty in Australia reports examined trends in poverty from 2000 to 2017. During that period, any reductions in poverty between ABS survey years among people in households relying on those payments were much less dramatic (See Attachment 2 and Davidson P, Bradbury B & Wong M 2020, op cit). Poverty rates among people in income support households moved within a band from 48-78% for Newstart Allowance, from 46% to 60% for Parenting Payment from and from 40% to 84% for Youth Allowance (in the latter case, poverty estimates were less robust due to small sample sizes). All things equal, the Supplement should have eliminated poverty among people relying on the maximum rates of those payments. However, as discussed previously many sole parents lost income from employment in the fourth quarter of 2019-20. This would also apply to some people receiving Newstart Allowance / JobSeeker Payment or Youth Allowance. In addition, since the poverty measure we use for this research takes account of housing costs, any increase in those costs in the fourth quarter could pull more people below the poverty line.

Reductions in poverty were less dramatic for ‘income support households’ relying on Age Pension (4% or 94,000 people) and Carer Payment (2% or 4,000 people), while poverty increased slightly among those relying on Disability Support Pension (2% or 14,000 people). Since its purpose was to compensate people participating in the paid workforce for (potential) income losses from COVID lockdowns, the Coronavirus Supplement was not paid to people receiving those pensions, though they did receive a $750 lump sum payment during the fourth quarter of 2019-20 (see Attachment 1). The slight increase in poverty among people relying on Disability Support Pension may be due to increases in housing costs.

It is noteworthy than poverty did not increase among ‘income support households’ relying on Age Pension, when (as discussed in Part 4.1 Age) it increased slightly among older people generally. This supports our earlier finding that the increase in poverty among older people was likely due to reductions in investment income, since income support households were likely to have had less investment income in the first place (See Part 4.1 Age).

Figure 12: Rate of poverty by social security payment received by ‘income support households’ in 2019-20, and change in poverty

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show average number of people in poverty by income support payment received by household reference person (generally the highest income-earning adult in the household) in 2019-20.

Blue bars show the increase or decrease in poverty from March to June quarters of 2020.

Income support households’ = Households in which over 50% of gross income is government cash benefits and those benefits are at least $180pw

Note that these changes in poverty cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures.

Reductions in poverty for household relying on Youth Allowance are not included, due to small sample sizes.

Figure 13: Number of people in poverty by social security payment received by ‘income support households’ in 2019-20, and change in poverty

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. Red bars show average number of people in poverty by income support payment received by household reference person (generally the highest income-earning adult in the household) in 2019-20.

Blue bars show the increase or decrease in poverty from March to June quarters of 2020.

Income support households’ = Households in which over 50% of gross income is government cash benefits and those benefits are at least $180pw

Note that these changes in poverty cannot be subtracted from the annual average figures.

Reductions in poverty for household relying on Youth Allowance are not included, due to small sample sizes.

(1) Poverty gaps for people in ‘income support households’

As discussed previously, the ‘poverty gap’ is a measure of the depth of poverty among those living below the poverty line. It is the average gap between their income and the poverty line, after deducting housing costs. Figure 14 shows the average poverty gaps for ‘income support households’ (as defined previously).

These average poverty gaps reflect the diverse circumstances of different types of families and are not adjusted for household size. As well as the differences between social security payments and poverty lines (Table 3 below) they are influenced by the composition of households in each group that fall below the poverty line.47In some cases, a large proportion of people belonging to a particular group are in poverty and poverty for those affected is relatively deep. In other cases, poverty among those affected may be deep but a much small number of people is impacted.

In 2019-20, the average poverty gap for income support households was $197 per week. Poverty was deepest (average poverty gaps were largest) among people in households whose main earner received Youth Allowance ($390 per week), Newstart Allowance / JobSeeker Payment ($269), and Parenting Payment ($246) and Carer Payment ($201). Poverty gaps were somewhat lower for Disability Support Pension ($156) and Age Pension ($118).

Figure 14: Average poverty gap for ‘income support households’, by payment type ($pw)

Note: 50% of median income poverty line, after subtracting housing costs. The red bars show average gap between the income of people in poverty and the poverty line in 2021-22 dollars per week, by social security payment received by household reference person in 2019-20.

This is a measure of the ‘depth’ of poverty among people living in poverty. Poverty gaps in this graph are the average gaps between the actual disposable incomes of people in poverty and the two poverty lines, taking account of any private income and housing costs. All family types (not only singles) are represented here. For example, many people receiving JobSeeker Payment were sole parents.

2) Comparison of payment rates and poverty lines

Above-average levels of poverty among households that mainly rely on social security payments are due in large part to the level of those payments, which usually sit below the poverty line. This means that a household relying on social security usually needs additional (private) income such as part-time earnings to avoid poverty. How much additional income is needed depends on the difference between social security payments and the poverty line and their housing costs (taken into account in the poverty measure used in this study).

Table 3 compares the maximum rates of social security payments available to hypothetical individuals and families with the poverty lines in the last two quarters of 2019-20. This takes account of the Coronavirus Supplement and lump sum COVID payments introduced in the fourth quarter.48Social security payments include income support payments for adults in families with low incomes (divided into the higher ‘pension’ payments such as Age Pension and the lower ‘allowance’ payments such as Newstart Allowance), Family Tax Benefits for children in low and middle-income families, and supplementary payments such as Rent Assistance for private tenants in low-income families. Individuals can receive only one income support payment but may also receive one or more supplementary payments depending on their circumstances. Table 3 shows how far above or below the poverty line households of various types receiving the maximum levels of social security payments were if they had no other income. For this purpose, we include Rent Assistance payments (except for older people who generally own their homes) and do not deduct housing costs from the poverty line.49This hypothetical comparison of poverty lines and payment rates is different to the poverty rate and poverty gap estimates in Figures 12 to 14, which are based on actual household incomes (including private income) and take account of actual housing costs.

Table 3: Comparison of poverty lines and social security payment rates ($pw in 2020).

Note: Amounts are in 2020 dollars. All children are 8-12 years old. All except households on pensions rent and receive the maximum rate of Rent Assistance. Minor supplements (e.g. Pension Supplement and Energy Supplement) are included. All except households on pensions receive Coronavirus Supplement in June 2020 and all receive one lump sum COVID payment (the value of which is averaged over the last quarter).

Youth Allowance (which was $48pw less than Newstart Allowance / JobSeeker in March 2020) is not included here.

Red = payment below poverty line; Green = payment above poverty line.

Just before COVID income supports began, (from January to March 2020), all of our hypothetical families had incomes below the poverty line.

Of these payments, the ones that fell furthest below the poverty line in percentage terms were:50We focus on the percentage difference between poverty lines and payments as this comparison takes account of the relative needs of different-sized families.

- Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment plus Rent Assistance for a single adult (27% or $134pw below the poverty line);

- Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment plus Rent Assistance for a couple with no children (21% or $152pw below the poverty line);

- Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment plus Family Tax Benefit and Rent Assistance for a couple with two children (18% or $187pw below the poverty line);

- Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment plus Family Tax Benefit and Rent Assistance for a sole parent with two children (15% or $119pw below the poverty line)

- Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment plus Family Tax Benefit and Rent Assistance for a couple with one child (15% or $136pw below the poverty line).

- Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment plus Family Tax Benefit and Rent Assistance for a sole parent with one child (11% or $67pw below the poverty line).

This reflects the low level of JobSeeker Payment (especially for single people) together with Family Tax Benefits that do not meet the minimum costs of raising a child (as measured in the poverty line). Youth Allowance (not shown in Table 3) for a single person living away from their parents was $48 per week less than JobSeeker Payment, so the difference between that payment and the poverty line was correspondingly greater.

Pension payments were also below the poverty line but closer to it, at:

- 4% ($19pw) below the poverty line for a single person and

- 3% ($25pw) below it for a couple.

Since pensions are regularly increased in line with growth in average male total earnings or increases in the cost of living (whichever is greater), and a one-off pension increase of $32 per week was paid to single pensioners excluding sole parents in 2009, these payments are much higher than ‘allowance’ payments such as JobSeeker Payment.51Saunders P & Wong M (2011): Op.Cit.

The maximum rates of social security payments available to a sole parent receiving Parenting Payment Single (not shown in Table 3) occupy a middle ground between JobSeeker Payment and pension levels.52Parenting Payment is only generally available to sole parents whose youngest child is less than 8 years old. Those payments (together with Family Tax Benefits and Rent Assistance) were therefore likely to sit between 4% and 15% below the poverty line.

These findings regarding the adequacy of social security payments are consistent with the ‘poverty gap’ analysis above.

Most payments were lifted above the poverty line in the fourth quarter of 2019-20, when COVID payments began

Table 3 also shows the differences between payments and poverty lines in the fourth quarter of 2019-20 (April to June 2020), after COVID income supports were introduced. This accounts for the impact of the Coronavirus Supplement and lump sum COVID payments, which was dramatic.

All of our hypothetical families receiving JobSeeker Payment were lifted well above the poverty line, with couples benefiting most in percentage terms. The largest gains were among people on:

- Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment plus Rent Assistance for a couple with no children (now 56% or $411pw above the poverty line);

- Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment plus Family Tax Benefit and Rent Assistance for a couple with one child (now 47% or $413pw above the poverty line);

- Newstart Allowance/JobSeeker Payment plus Family Tax Benefit and Rent Assistance for a sole parent with one child (now 36% or $228pw above the poverty line);