Housing affordability takes a hit - regionally and globally

A new report from the ACOSS/UNSW Sydney Poverty and Inequality Partnership shows that regional rents are now 18% higher than 2 years ago, at the start of the COVID 19 pandemic. Given that wages have only risen by 6%, the report concludes that regional rental housing affordability has significantly worsened during the public health crisis.

Every Australian capital city and regional area has seen rent rises during this crisis period far in excess of wage increases or CPI-linked payment adjustment, with the exception of Sydney and Melbourne.

State-level figures show that the situation for regional renters in Tasmania and Western Australia is particularly difficult because of even larger housing cost increases.

The report, COVID 19: Housing market impacts and housing policy responses – an international review compared the experiences of Australia and seven other case study countries – Canada, Germany, Ireland, New Zealand, Spain, the UK and the US. It found that all followed similar paths in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic by providing emergency income support, along with more direct housing and homelessness interventions.

These temporary actions helped to avoid the housing market disorder, mass insecurity and homelessness which were widely anticipated everywhere at the start of the crisis and meant that vulnerable tenants and homeless people were protected.

However, once the initial moratoriums on rent increases and evictions were lifted, the report also shows that nearly all the countries reviewed experienced rapidly accelerating rent inflation – at rates higher than anything experienced over the previous decade. In Australia, the UK and US, 2021 rent inflation reached levels unseen since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis or GFC.

The report highlights that, with house prices also having risen sharply during the crisis in most of the researched countries, housing affordability pressures are now generally even more acute in 2022 than when COVID first hit. And this after a decade when Australia, like most of the other countries covered, had already seen intensifying rental housing stress.

According to ACOSS CEO, Dr Cassandra Goldie:

“Soaring regional rents are compounding financial stress for many people on low incomes or receiving income support payments. Regional rents are rising at rates far above the national average yet are only indexed to capital city rents. This means regional renters on social security will be facing cost of living hikes well above their CPI-linked benefit increase.

“With private rentals already in short supply before the recent devastating floods, soaring rents, and a severe shortage of social housing options, we’re in the middle of a renting crisis in many parts of regional Australia. In flood-affected areas, it’s clear the rental market cannot house the families on low and middle incomes who have been made homeless temporarily - the real concern is that this then becomes permanent.

“We need immediate Federal Government action to help house people made homeless in flood-affected communities. But COVID and the floods are only aggravating a national rental problem that has been building for years. After a decade of Commonwealth neglect on social housing we badly need a major national building program that starts to remedy this, with a sizeable part of the investment going to the regional centres facing the greatest stress.”

Report lead author Professor Hal Pawson said:

“Just as in most other countries in our study, Australia’s emergency income protection and also housing policy measures triggered by the pandemic went well beyond what anyone would have previously imagined. Just for a brief moment we had a tantalising glimpse of cities with street homelessness greatly reduced and a rental housing market where evictions were drastically cut. But since the experience has prompted virtually no permanent reforms of social security or rental housing regulation, governments appear to have resisted learning lessons from the episode.”

Emma Greenhalgh, Chief Executive Officer of National Shelter, said:

“This report demonstrates the missed opportunities of the past two years to capitalise on the initial positive responses by governments to address housing and homelessness issues during COVID, and create a housing legacy from the pandemic by investing in social and affordable housing. We are in a national housing emergency that has been a long time in the making, compounded by COVID and climate disasters. There is a lack of urgency by the Federal Government to this crisis. The development of a national housing strategy to respond to this crisis is critical.”

Mission Australia CEO Sharon Callister said:

“This report confirms that, just like other countries, it has never been so difficult to find an affordable home to rent in Australia – particularly in our regional areas. The end of the temporary increases to income support and the rapidly increasing affordability pressures are putting people at greater risk of homelessness. We continue to see people in low-paid, insecure and casual work living precariously and unable to afford the basic necessities, especially housing.

“Mission Australia calls on the Federal Government to lead a national plan to end homelessness. We urgently need to move Australia onto a credible path to end homelessness and provide everyone with a safe and affordable home through significant investment in social and affordable housing.”

Read the full report at: https://bit.ly/3qcpk97

Find out more about the poverty and inequality partnership at http://povertyandinequality.acoss.org.au

Key Findings

- By late 2021, rents were at historically high rates in Australia, the UK, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand and the US.

- Between early 2020 & late 2021, house prices rose in all 8 countries researched for this report – Australia, Canada, Germany, Ireland, New Zealand, the UK and the US.

- There has been no price decline since COVID struck, unlike the GFCwhich triggered major and prolonged downturns in Ireland, Spain and the US.

- By Q3 2021, annual nominal house price inflation had reached 22% in Australia and New Zealand, 18% in Canada and USA, 12% in the UK and 11% in Ireland.

- By end 2021, annual rental increases were higher than 8% in Australia, the UK, Ireland, New Zealand and the US – in most of these countries the fastest rate of rent inflation since 2008.

- In 5 out of the 6 countries covered in this report for which national statistics are available, nominal rent increases exceeded wage increases in the 2-year period to late 2021, therefore damaging rental affordability.

- In 2020 and 2021, property prices and rents increased faster for detached houses than for apartments, and for regional rather than urban areas, probably reflecting the rapid rise of remote work that enables workers to move away from urban areas.

- The other 2 countries researched for this report saw different outcomes. In Germany, house prices were similar to pre-pandemic, while in Spain price growth remained subdued. Similarly, the rental market in Germany was relatively unaffected by the pandemic, while in Spain rents continued to decline in nominal terms.

- This is because Germany has an unusually resilient economic and housing system due to conservative mortgage lending and a strong social safety net. In Spain, however, the housing and rental market suffered from heavy damage sustained by the dominant tourism industry

- All 8 countries researched took far-reaching measures to maintain incomes and economies during the first 2 years of the pandemic, including through increased social security, introducing new temporary assistance payments, through furlough or wage subsidies, and financial sector support from major banks.

- Most of the countries researched also took measures to safeguard housing systems & prevent homelessness, such as deferred mortgage payments, rental eviction moratoriums and emergency accommodation for people experiencing homelessness.

- Some countries such as Australia and the UK offered direct government-funded housing market stimulus, which was misdirected as this compounded record low interest rates in inflating demand, meaning that many people were locked out by resulting house price inflation,

Key graphs

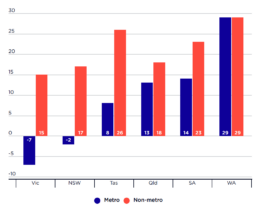

SOURCE: Domain.com.au, specially commissioned analysis

SOURCE: Domain.com.au, specially commissioned analysis

Median advertised rents by state/territory in Australia, 2019-2021

This graph shows the phenomenon of regional rents ‘outperforming’ the relevant capital city in Australia from 2019-2021. This was especially marked in New South Wales (+17% versus-2%), Tasmania (+26% versus +8%) and Victoria (+15% versus -7%). Also notable is that Western Australia, where geographical isolation and a closed border largely enabled avoidance of economic restrictions during the first two years of the pandemic, the pattern was completely different.

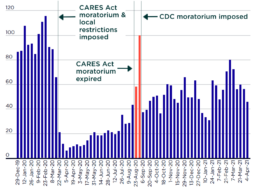

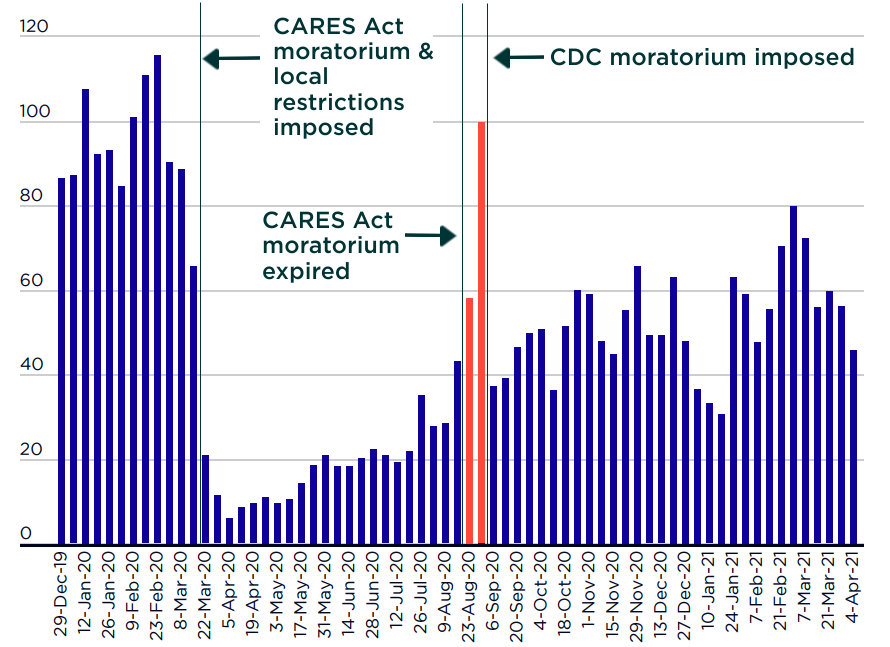

Weekly eviction filings in 2020 and 2021 as a % of pre-pandemic norm, USA

In the USA. series of eviction moratoriums from multiple agencies and levels of government were introduced over the period of the pandemic, many of which had lapsed by July 2020. Nationally, Congress included evictorion moratorium in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which commenced on 27 March 2020. This appled to 'federally related properties', including propoerties supported by federally-backed finance or occupied by tenants with Housing Choice vouchers. For the properties it coered, it prohibited the commencement and enforcement of eviction proceedings for unpaid rent until 23 August 2020.

From 4 September 2020, two weeks after the CARES Act expired, the CDC National moratorium was imposed, which covered all tenants meeting certain income and hardship criteria, including that they had applied for government assistance and would be at risk of homelessness or overcrowding if evicted. Tenants seeking the moratorium protection were required to declare their eligibility to their landlord. Like its CARES Act predecessor, the CDC moratorium prohibited landlords from commencing or enforcing eviction proceedings for non-payment of rent. This moratorium was supposed to expire on 31 December 2020, but it was extende to 31 January 2021, and prolonged a further three times by the CDC. It was eventually struck down on 23 August 2021, and in early 2022 a handful of municipal moratoriums, mostly in California, remain.

This figure analyses evictions data sourced by Eviction Lab, Hepburn et al. (2021), who calculated that eviction application rates in the period March-December 2020 were 65% below their historical average, with the greatest reduction in the period of the CARES Act moratorium and early sub-national moratoriums. The spike in eviction applications in the two-week gap between the two national moratoriums also indicates the strong direct effect of these restrictions. Over the period of the CDC moratorium, Rangel et al. (2021) calculate that eviction applications were down 53% on historical average levels. After its sudden cancellation, eviction application rates lifted, although only to 63% of their historic average (Hass et al. 2021). Over the combined moratorium periods an estimated 2.45 million evictions had been avoided by early 2021 (Rangel et al. 2021).

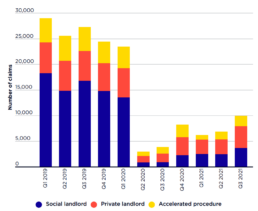

Possession Actions in England, 2019-2021

UK governments did not regulate rents during the emergency, and a public campaign for the suspension or cancellation of rent arrears was rejected. Instead, various measures of financial assistance were implemented: in March 2020, Local Housing Allowance was increased to cover 30% of market rents (restoring an earlier link, severed in 2016), and in late 2021 English local authorities were allocated additional funds to support low-income tenants still in rent arrears. The Scottish and Welsh Governments implemented loan schemes for the payment of arrears: the Scottish scheme paid up to nine months’ rent arrears, for repayment over a period of up to five years.

Government data on termination proceedings (‘possession claims’) in England show a dramatic reduction in the pandemic period. Possession claims by all landlords in Q2 2020 were down 88% on the same quarter the previous year, and claims for 2020-21 were down 79% on the previous year; however, the largest reductions were by social housing providers, not their private landlord counterparts. Claims by private landlords or otherwise using the ’accelerated procedure’ (largely no-grounds claims by private landlords) were down 80% in Q2 2020 year on year, and by the fourth quarter the rate was down 40% year on year.

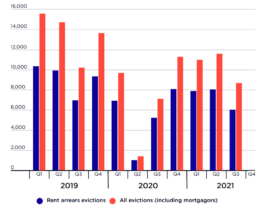

Evictions, Spain, 2019-2021

In Spain, from October 2020, the Spanish government paid compensation to landlords of non-paying vulnerable tenants protected by the moratorium, based on losses relative to average rents. It also limited the application of the eviction moratorium to lawful tenants, after squatters were able to claim protection under the first version.

This graph shows that Spanish evictions in the second quarter of 2020 dropped dramatically – especially evictions for rent arrears, which were down 90% year on year. Subsequently, however, evictions rose, to 75% of the previous year’s level in Q3, and exceeded the previous year’s level in Q1 2021.

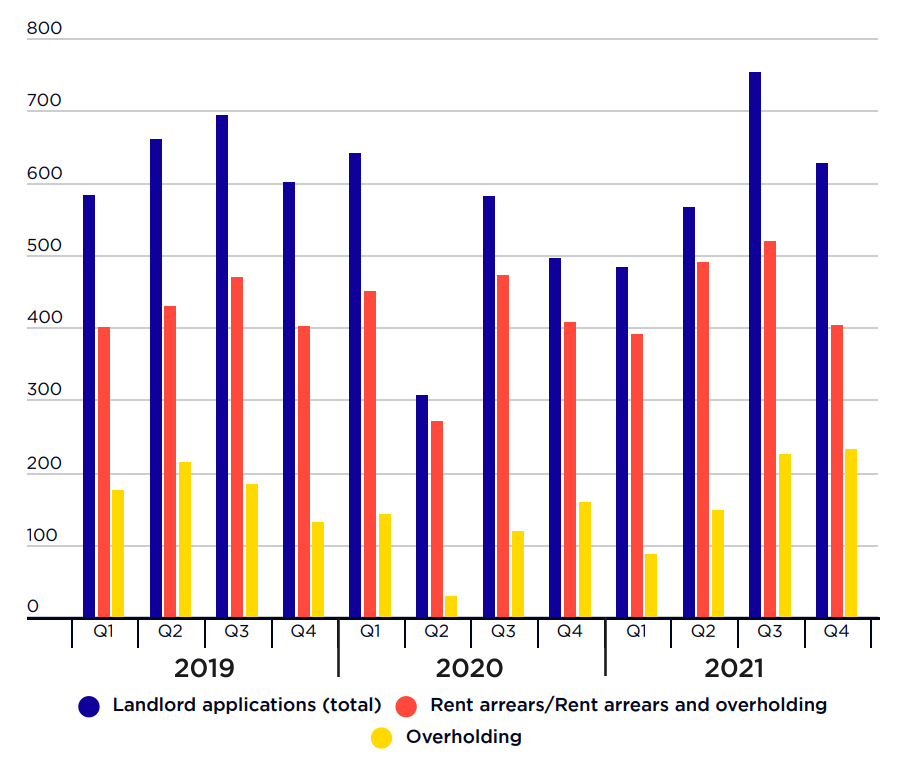

Rent arrears and overholding applications, Ireland, 2019-2021

Ireland’s COVID-19 eviction moratorium was enacted on 27 March 2020. It was both broad and strong, prohibiting landlords from giving termination notices on any grounds and stopping all evictions for the duration of the (initial) emergency period. Rent increases were also prohibited. These prohibitions expired 1 August 2020. However, provision was then made for tenants in COVID-related hardship to claim, by declaration to their landlord and the Residential Tenancies Board, protection from eviction and rent increases until July 2021 and, if termination proceedings were taken then at that stage, a longer 90-day notice period. The declaration required the tenant to make contact with advice services to assist making repayment plans. The Irish Government did not implement new rent relief schemes, but did change eligibility rules to make the Rent Supplement payment available to persons receiving the Pandemic Unemployment Payment.

Tribunal applications for rent arrears and termination orders, New Zealand, 2020-21

In New Zealand in 2020, a national moratorium was legislated that for three months stopped the commencement and enforcement of eviction proceedings on most grounds. Prohibited grounds included the landlord or an incoming purchaser using the premises for their own housing, reflecting the heavy restrictions on household movement imposed by New Zealand’s public health orders. Termination proceedings for anti-social behaviour and other urgent grounds remained allowable, as well as for rent arrears – but only where tenant arrears equated to more than 60 days. Rent increases were prohibited, and the government encouraged rent negotiations between landlords and tenants in hardship, but did not set out a special regime or guidance for them. It also temporarily doubled (to NZ$4,000) the maximum amount lent to tenants under its Rent Arrears Assistance scheme. The moratorium expired 25 June 2020.

This figure shows that applications by landlords for rent arrears and termination orders dropped by 55% and 67% respectively during New Zealand’s moratorium, when compared with the previous quarter. Subsequently, application rates rose only moderately in late 2020, before easing once again in 2021.

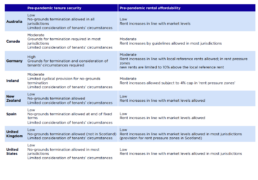

Pre pandemic tenure security and rental affordability

This table shows the crisis responses that were implemented in Australia, Canada, Germany, Ireland, New Zealand, Spain, the UK and the USA specifically aimed at protection for rental housing residence. It gives a high-level overview of the relative levels of regulatory assurance of these aspects of renting for each of these countries, necessarily passing over some significant differences in the legal mechanisms used between countries, and some significant differences between jurisdictions within countries.

For indicators of tenure security, the table indicates whether landlords may take termination proceedings without disclosing reasons or where these may be invoked only on certain legally prescribed grounds, and the degree to which tenants’ circumstances are considered by the relevant tribunal in termination proceedings. This may be limited by laws that make termination in some rent arrears and no-grounds proceedings mandatory (as in most jurisdictions in Australia, the UK and the US), that restrict the tribunal’s discretion to decline termination (as in New Zealand), or that put the onus on tenants to dispute termination proceedings (as in some Canadian provinces, Ireland and Spain).

Income protection variation

This table asks which types of income protection variation measures precipitated by the COVID-19 crisis predominated in Australia, Canada, Germany, Ireland, New Zealand, Spain, the UK and the USA. It also looks at whether pre-existing policies were important, if there is any evidence that specific policies were prematurely ended (i.e. where the factors originally prompting intervention remained in evidence); and whether policies introduced as a result of the pandemic are likely to continue in the longer term.